written by Maria Vogel

A few years ago, you gained notoriety for your blog, ART BLOG ART BLOG. When that started did you feel that it created an expectation around your actual physical work?

I think my main concern with blogging was trying to draw a parallel between looking and making, and thinking about how all of it is interconnected. One thing I did with the blog was make my name overly present. Every time there was a post, it would read, “posted by Joshua Abelow.” There are thousands of posts and even the URL is joshuaabelow.blogspot.com. When I started the blog back in 2010, I was going through this intense phase, most obvious in the drawings, where I was making satirical self-portraits of the “Artist.” I was deeply frustrated with art and my own art in particular. When I discovered Paul McCarthy’s “Painter” (1995) for the first time in 2006 or 2007 a light bulb went off and I realized I could make paintings and drawings from a satirical stance. I realized I could invent a character (or characters) and make work from that character’s point of view. This was a revelation. I was dealing with the ego, the maniacal nature of the artist. I saw the blog as perfectly in tandem with that – just posting, posting, posting, just obsessively posting like somebody who’s lost their mind. It was informational and also performative. When Instagram took over the world, blogging instantly became antiquated. So, I got the idea to start Freddy [Gallery]. Freddy is another way for me to address the maniacal, artistic persona. It allows me to be more specific with my curatorial ideas, but my own name remains low-key. In a way, I’m operating from my character’s viewpoint. It’s basically an extension of what I think about in the studio, but I get to directly involve other artists, which is a lot of fun.

Looking at your works, your process appears very methodical. Do you leave any room for intuitive creation while you’re working?

Yeah, definitely. Working with systems can open up a lot of possibilities. No matter how much you try to control oil paint you really just can’t. It’s just the nature of the medium and that’s a wonderful thing. There’s so much room for the unexpected. Drawing is also an intuitive process. I never know exactly what’s going to show up on the paper and that’s what makes it interesting.

Many of your paintings are distinctly colorful, however, when you work with a graphite pencil it’s always the same. Is there a process behind deciding in which way you want to portray something?

JA: My drawings are entirely composed of lines and I make them quickly. The paintings are slower. I work on them bit by bit over a period of weeks or months. There’s a lot more process stuff involved with making the paintings and there’s a good amount of mindless labor. Making a drawing can be a release. I just grab the pencil and make something without any waiting around. It’s direct.

You address the rise of technology in many of your works but you don’t seem to use technology itself when you are creating. How do you view technology’s role in art today?

JA: One interesting thing that I sort of go back to, it’s one of those things that’s so basic, is the continuum of art. I’m interested in how traditional mediums like oil paint or graphite can be used in the 21st Century, in this high-speed technological landscape. Even if you’re an artist who’s making oil paintings and you take the position that you have nothing to do with digital technology because you are a painter and you deal with paint, it’s nearly impossible to escape technology’s reach. If you’re making paintings and participating in the contemporary art world, then that means your work is being digitally reproduced. It means that if you have an exhibition in a public setting, unless photography is banned, people are taking photos of your work with their phones and then these digital reproductions of your work are going out into the world at an unprecedented speed. And a lot of people are seeing these reproductions rather than the original works. In my work, I try to address that in the works themselves. The Running Witch paintings from 2014 were made with the awareness that these things were going to exist in a physical space as well as in the non-reality space of the Internet. I really like the idea of these witches running around online all day and night. That to me is the sweet spot.

How have the shifts in our culture socially and politically played into your art since you began?

With the new president in office, there has been this tremendous shift in how we understand the world. Every action (or non-action) is viewed through the lens of politics. After the election, at least with my painting, I’ve tried to address the political climate by making paintings as plain as possible. There is still political content, but it’s not in your face. I’m interested in abstract paintings that can speak to what’s going on without hitting you over the head with didactic political propaganda. I think the Trump presidency has re-energized my interest in subtlety.

Is it becoming increasingly harder for you to create something with a shock value – how do you continue to include loaded imagery in your works?

JA: I was sort of just talking about that, but doing the opposite – making work as plain as possible. Even the paintings I make with loaded imagery are painted in a very plain way. I like when there is tension between the image and the way an image is created. That’s something I’ve always admired about the work of Andy Warhol or Christopher Wool.

What was your intention in opening your space, Freddy Gallery, in upstate New York?

JA: Freddy opened in Baltimore during the summer of 2014 and I had a bunch of different reasons for starting it. I wanted to do a project that was more anonymous than what I’d been up to with the blog. In the very beginning, nobody knew who was behind the gallery, but that didn’t last long. It was really interesting to sort of play with an alter ego, where my true identity was a secret, that was fun. What I found quickly is that in Baltimore, the art community is very small so word on the street spread and everyone knew it was me within a couple of days [laughs]. I also started Freddy in part because I had long-time interest in Baltimore as a creative city. Over the years, I’d spent a lot of time hanging out in Baltimore and I was always refreshed by the DIY attitude. Compared to the New York lifestyle, it’s a lot more laid-back. The commercial concerns that you feel when you live in New York simply don’t exist there. After about a year and a half of doing Freddy in Baltimore, a friend showed me an old church that was for sale up in the Catskills. I took a drive up there to check it out and basically just jumped on the opportunity. So I left Baltimore and opened Freddy at the church two weeks after I moved in. That was two years ago.

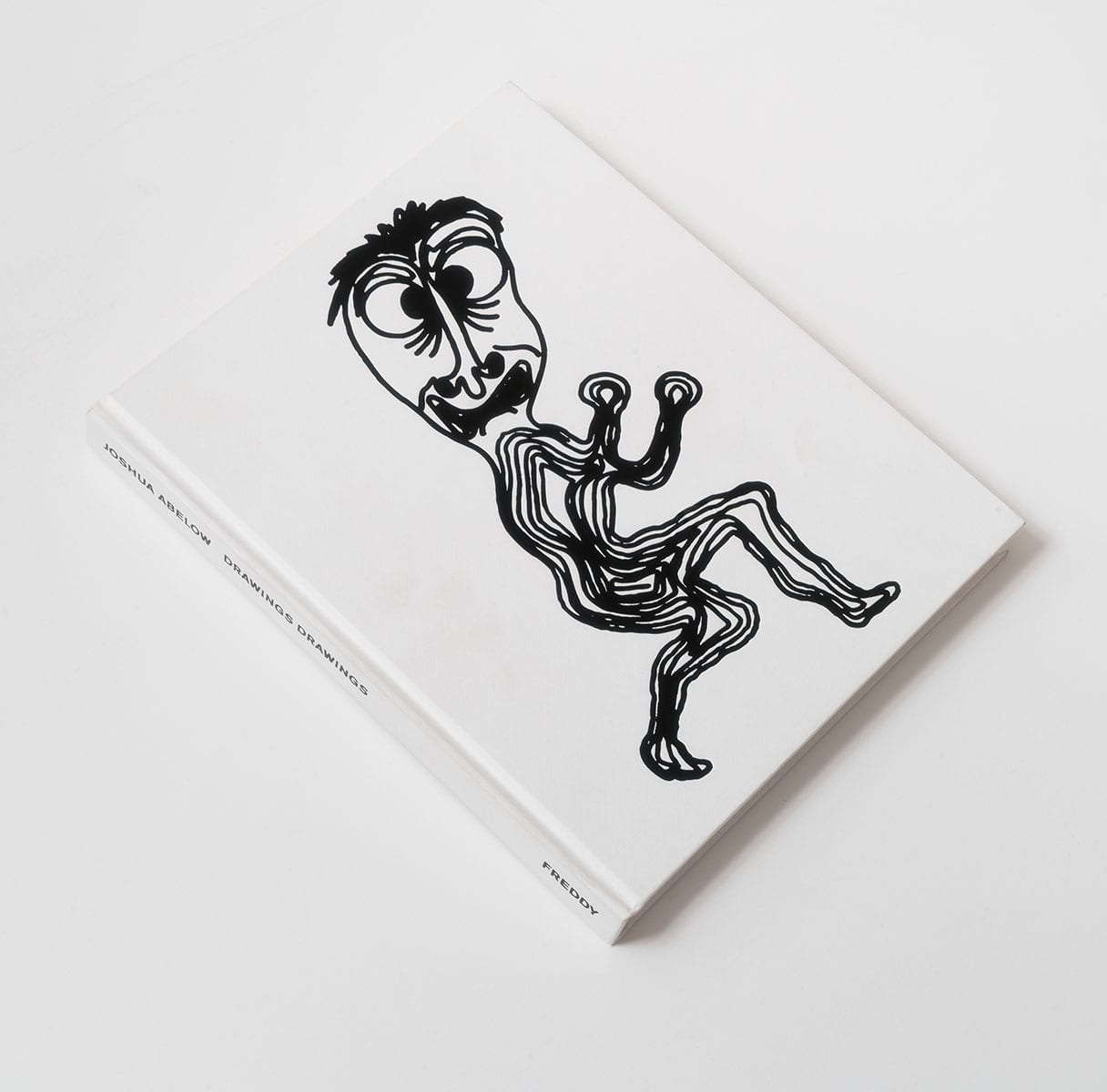

Your book DRAWINGS DRAWINGS was just published, covering over a decade of your work. Can you talk a little bit about what this book means to you and how it came about?

The simple framework for my drawings hasn’t changed since 2004. In a way, the overarching subject matter is mutation and/or transformation. Like what happens when you do the same thing over and over again for a sustained period of time? How does the work change and why? That is the basic hypothesis for a lot of the things I do. So, putting the drawings in chronological order in the form of a book seemed logical. There are clear “chapters” in the book, although, in a way, it’s just one big run-on sentence. When my father passed away last year, I decided that I had to make this book happen one way or another because I wanted to dedicate it to him. That was the big event in my life that gave me a sense of urgency to make it happen. The book is called DRAWINGS DRAWINGS as a sort of tongue-and-cheek reference to ART BLOG ART BLOG. In the book, each drawing is repeated once, so that when you turn the pages you see the same drawing on the right repeated on the left. That was a way for me to acknowledge that these aren’t drawings; they are reproductions of drawings. It slows down the viewing. You end up looking at each drawing for more time when there’s two of them and your brain starts playing tricks and you don’t know if the drawings are the same or not.

What’s next for you? What are you excited about?

I’m excited to get Freddy’s programming started. The first show of the season opens May 12th. I’m showing a series of dog heads by New York artist Cynthia Eardley. The sculptures are based on Cynthia’s happy memories of her dog running around in the mountains in the summertime and I just think that’s a really beautiful image.