Maria Farrar brings a multicultural, globe-spanning perspective into her spirited practice. Born in the Philippines, raised in Japan, and now residing in London, Farrar’s canvases forge her formative experiences. The simply rendered figures and quotidian moments Farrar creates have a subtle power to them that hold as much insight as they do intrigue.

Your works contain various cultural influences. How do you combine various styles onto the same canvas and what do they all mean to you?

Stroopwafels was based on motifs from Holland and Japan. A pastiche of a trip to Amsterdam, it combined things that I saw or wanted, or wanted but didn’t want to have, from the Rijksmuseum and gift shops. There was a lot of cheese and wafel stores on the streets and the museum was stuffed full of incredible things that I didn’t know what to do with my excitement. I was thankful that I had a studio back in London to paint it. That way I got to take a bit of it home. I also saw a big exhibition of Hockney and Van Gogh there, which maybe gave me the idea for bolder colours. A glass vase at the Rijks had this tinted dancing frog and bunny that made me smile. A month or so later, at a manga exhibition of Japanese cartoons at the British Museum there were Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans from the 12th century – one of the very first manga. As Holland was the only port during the 300years of trade closure between Japan and the West, a cartoon must’ve made it’s way to this Dutch vase around the 17th century across the ocean. It feels a privilege to be able to paint it.

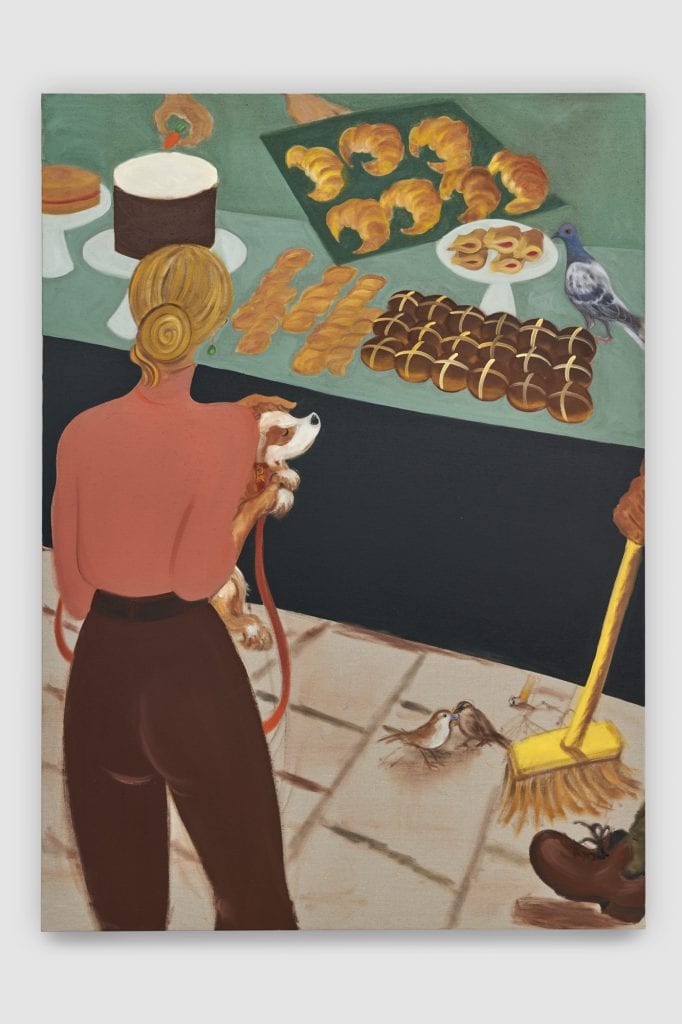

I love balancing a stroopwafel onto a coffee cup and waiting for the caramel to melt before eating it, a custom a friend from Holland told me about. The cakes I painted in the last couple of years all have great stories. The monk who baked the first hot cross bun in the 12th century to the child who gets to be kind for a day for finding the ring in his slice of Gallette de Rois. The birthday cake that the moomin mama insists on taking when they flee the village in Comet in Moominland reminds me of my mum’s multicoloured birthday cakes she made for me as I was growing up. Cakes have so much love, and like painting its ritual and culture everybody can understand, even without language.

What Art Historical movements does your work reference?

I’m guilty of not really looking at dates of artworks and go along with whether I like or hate them. They change all the time but I’ve always liked Rothko, Chagall and Man Ray. Like for many, Rothko’s paintings redefine possibilities of colour and get a shock about its strength. Every time I got to the Rothko rooms at Tate modern I realise that I forget that colour alone could have so much power. Chagall’s dreamy compositions remind me to take dreams seriously. Also a reminder not to underestimate how much there is in your own mind. With so much to see – from nature, from cheaper travel, images online, reproductions, museums – what’s contained in your own mind at the end of the day sometimes gets disregarded. It’s surprising to wake up in the morning with an image and wonder where it had been hiding when you were awake! When I’m stuck with a painting I always turn to Edouard Manet, especially Olympia. His paintings helps keep focus on the bigger picture, to let go of how I feel about my own petty shortcomings. On the other hand the old cave paintings in France seem to have a lot in common with our age than some other periods in art history. perhaps this is one of the most unique things about history that we understand the psyche of the people in certain times and yet other things that the same people did we haven’t got a clue how they might have felt.

Your work invites negative space into the composition, often leaving parts of the canvas blank. Why is this?

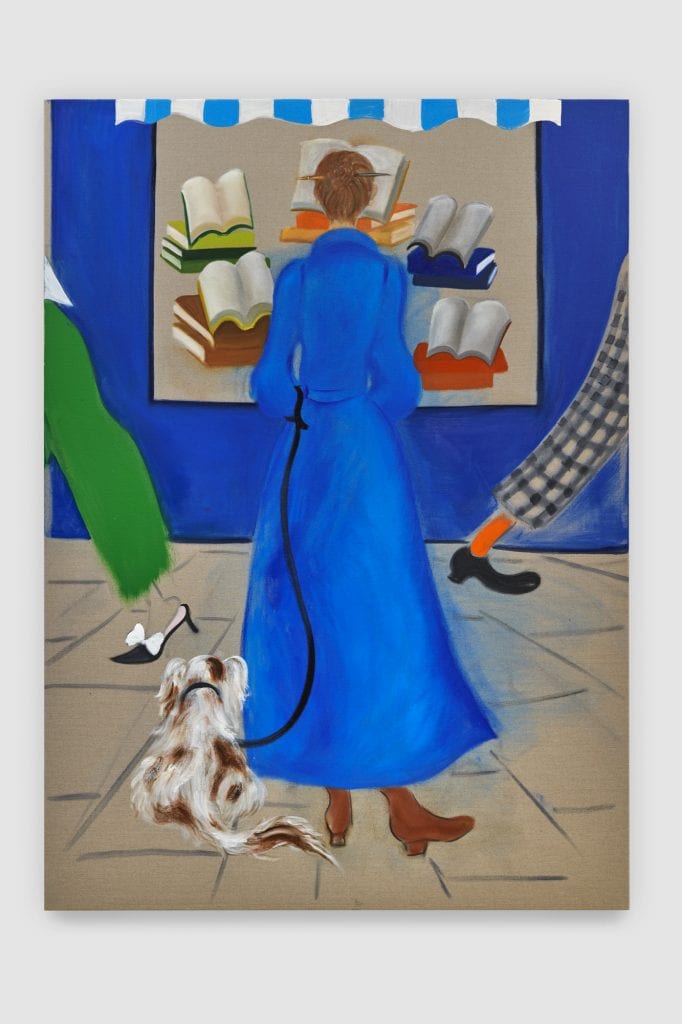

The patisserie series I first painted did have a lot of canvas unpainted. I remember as a kid, once a month a special edition of the cartoon strip I followed came out in print and only the first few pages were printed in colour. I looked forward to them as I discovered skintones, colour of their homes and clothes and it felt like a real treat. I think of colour in paintings as a luxury, the less you see, the more you want.

I saw a breathtaking sketch by Leonardo Da Vinci of Mary Magdalene at the British Museum. Twisting and turning heads effortlessly coming together to make a composition. It was an unfinished study with an allure of its very own. The early stages of an image, the first stroke of the material, the unpainted seemed an interesting idea to go along with.

What is your process like? How do you begin a work?

Getting the paintings’ motifs together from real life begins early – a photograph/drawing/memory from months or even years back. They get loosely drawn out with a neutral tone on a big canvas, then usually abandoned for a few weeks, a lot like waiting for sourdough to rise, and I can I work on something else. When I come back to it some ideas would have disappeared and others would have replace it. This always fascinates me, how what seemed amazing at one time fade away and what seemed stupid become clever, it reminds me that I am just a series of dying and reforming cells. It saddens me sometimes that even oil paint has a timespan really, despite it being longer than most things, like the human race.

From where do you draw inspiration for your works?

Travel: it could be as close as the cafe round the corner (drawing on different tones of tissue), or a 12 hour flight to Shanghai (where I got the idea for the first series of pastries.) I think travel is the only way to see colours, forms and stories for what they really are. Sometimes an answer to a difficult painting comes in a hotel room abroad. Half asleep I thought about how I might sort out a painting, and got excited about coming back to the studio. On the other hand there needs to be a balance, there is a lot I could learn from just seeing how paint might look on the canvas and the hours in the studio.

What’s next for you?

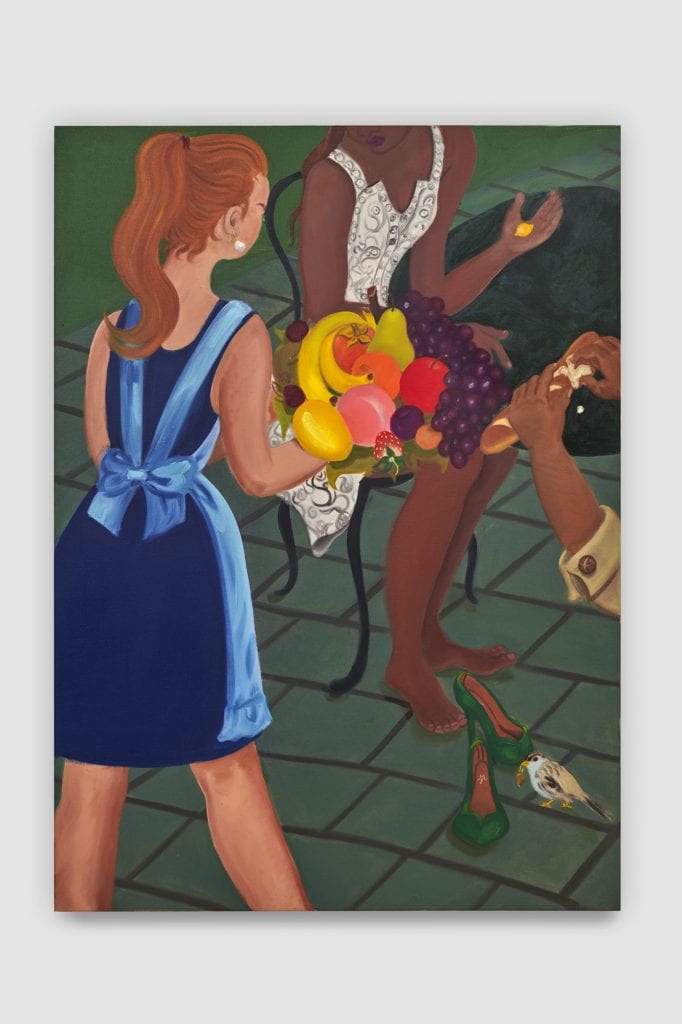

Someone asked why don’t I make smaller pieces and it was a really interesting question. I think it’s much easier to forget about the immediate effects of colour and form and think too much about the story in small paintings that, even though it’s a lot less physical energy, there’s a lot more for me to work on. I also want to spend a few weeks in my mum’s village in the Philippines in January 2020. About 10 years ago I made watercolours of tropical fruits and brought them back. They didn’t feel like much at the time but without having painted those mangoes, dragonfruit and bananas I wouldn’t have made some of the paintings I painted today. It reminds me that everything is connected – what you do and what you choose not to. The best events are those where you don’t actually know what the effects might be.

At the end of every interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

Milly Peck. She’s an old friend and a wonderful sculptor.