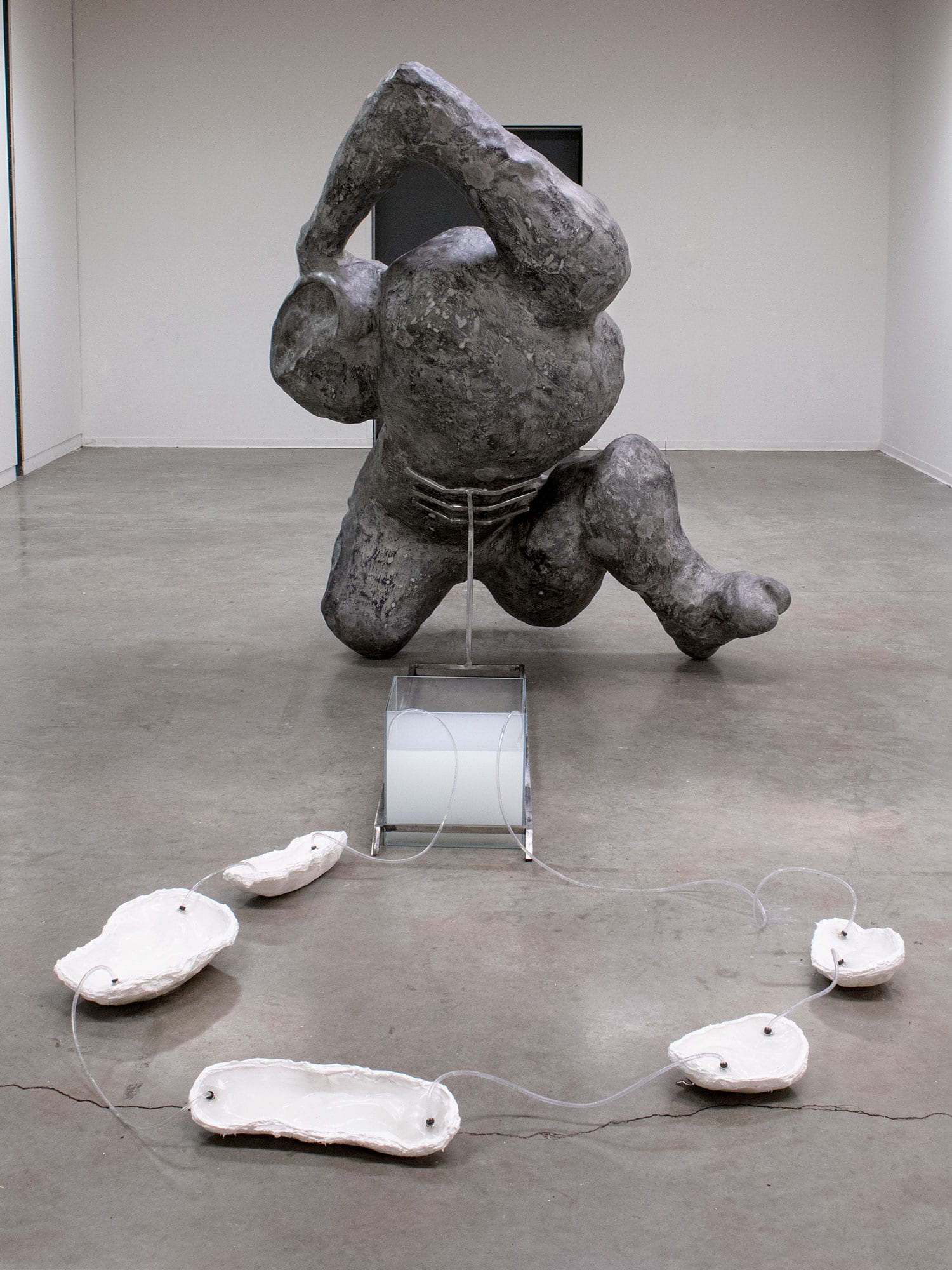

Nicki Cherry‘s abstract forms tend to evoke feelings more so than recognizable figures. Her large-scale sculptures provide an overwhelming sense of familiarity – building a rapport with the viewer that comes through the individual’s interpretation of her work. The monochromatic color choice adds to this. Because of our own association of certain colors with certain feelings, she is able to take advantage of our inherently human relationship with color, and thus translate it into an appreciation for her art. From her smaller works to the larger ones, materials differ, but each element is carefully considered as she “think[s] of it as skin.” The anthropomorphic aspects of her work offer a different perspective on these alien forms. Not fully human, yet not always fully abstract.

Tell us about yourself. Where are you from and when did art first enter your life?

I grew up in a college town in Indiana. I always loved to paint and draw in my childhood, but I wanted to be a scientist. I went to undergrad at the University of Chicago and spent the first half studying physics and mathematics. My third year, I enrolled in a sculpture class and became completely obsessed with how difficult I found it; it was both liberating and maddening that sculpture allowed use of any material.

Courtesy of the artist.

What is your preferred medium and how did you come to work in this material?

My larger forms are made out of carved polystyrene that is layered with fiberglass, concrete, and epoxy resin. I’ve always been interested in making forms that have an indexical relationship to the viewer’s own body. Foam is an easy way to make large forms that I can move around myself and easily manipulate. I like the awkwardness that comes out of trying to transform a flat stock material into a voluptuous, organic form. In the past year, I’ve been learning how to blow glass and have been experimenting with how to incorporate glass objects into my sculptures. I took several classes at UrbanGlass in Brooklyn as a sort of post-grad-school therapy. It’s a much more collaborative process than I’m used to in my studio, which I’ve enjoyed.

Courtesy of the artist.

How do you source the material for your work and what is important to you when seeking it out?

The more foundational materials I use in my larger works—like fiberglass, silicone, cement, and wax—are all things I think of as skin. I use these materials to layer on color and luminosities on my forms. Other materials—like latex tubing, steel armatures, pieces of hardware, and tulips—are. I’m interested in how close or disparate they can feel as prosthetics to the bodies of my sculptures. I try to carve out small gestures with nonsensical functions within larger works, like using a bandaid to repair a dried flower or propping up a heavy work with a cast wax tulip. The materials and systems in my work often speak to a human desire to exert control over our bodies and minds.

Courtesy of the artist.

What is a day in the studio like for you?

I spend a lot of time alternating between fussing over objects, moving materials and forms back and forth between pieces, reading, and looking at the work. It takes a while for each work’s final configuration and form to reveal itself. My favorite days are ones spent getting totally sucked into fabrication. I really enjoy the physical aspects of making, when it feels a bit like an endurance sport.

Courtesy of the artist.

If you had someone describe your sculptures in three words, what do you think they might say?

Alien, saturated, bodily.

Courtesy of the artist.

From where do you draw inspiration?

Part of my process is absorbing and hybridizing piecemeal bits of text and imagery. My work in the past year has fixated on Hieronymus Bosch painting, “Cutting the Stone,” which depicts a doctor cutting a tulip bulb out of a patient’s head. More recently, I read Lucian of Samotosa’s text “True History”, which is a 1st century Levantine text that’s often described as the first sci-fi novel. The text has crazy descriptions of moon aliens that deliver their newborns through an incision in their legs. Images from Ursula Le Guin’s “The Left Hand of Darkness” and Han Kang’s “The Vegetarian” have been floating in my head during quarantine.

Courtesy of the artist.

What, if any, historical movements or individuals have influenced your work?

I’ve looked to the way Rachel Harrison uses found objects and color, Candice Lin’s organic materiality and living processes, Huma Bhabha’s forms and materials, David Lynch’s bizarre worlds, Jim Henson’s creatures, David Bowie’s costumes and personas.

Courtesy of the artist.

Have you always worked in your current style?

I try to avoid thinking about my own work as having a particular style, as I find that can get me stuck in working with limited forms and materials. I would say the initial pieces that have set me into my current trajectory were made in 2014, and my work has evolved from there.

Courtesy of the artist.

What do you have coming up?

I’m planning a larger work tying a circulation system and blown glass objects together that I’m hoping to start fabrication on once it’s safe to work in glassblowing studios during the pandemic. Right now, I’m working on some smaller pieces that started as material studies and some larger works that stemmed from a desire to make big vessels.

Courtesy of the artist.

At the end of every interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

There’s so many! Azza El Siddique, Lauren Jeyoon Lee, Cole Lu, Coral Saucedo Lomelí, Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski, Kerri Conlon, Alfredo Diaz, Saskia Krafft, Catalina Ouyang, Ye Qin Zhu, Douglas Rieger.