Lily Simonson’s bright compositions of an underwater world we know of and are yet so detached from, allow viewers to explore the depths of the ocean floor and the mesmerising array of shapes and colors that make part of it. Her passion for science is reflected in a series of vibrant paintings, which she develops through on-site exploration in the most remote places on our planet, as well as collaboration with professionals in Marine Biology. The artist grapples with ideas such as climate change and resource extraction, where underwater ecosystems may never directly encounter a human being, yet they’re irreversibly affected by our ways of life.

To the Lighthouses, Costa Rica Margin (2018), Courtesy of Lily Simonson, Photographer: John Janca

Where are you from originally and when did art first enter your life?

I was born in Washington DC. My parents are artists and I was raised on art, but I also came from four generations of activists and early on I wanted to become a civil rights lawyer. I changed course and decided to become an artist in high school, after learning about the Dada idea, that art can be a way to fight injustice. That concept was out of vogue in the art world for a long time, but I think the Black Lives Matter movement is pushing artists to re-examine their roles in society. As a white artist I’m reluctant

to take up space in any way right now, but at the same time it’s important we all openly reflect on how our work can be used to dismantle tools of oppression.

Venus at Her Mirror, East Pacific Area (2018), Courtesy of Lily Simonson, Photographer: John Janca

In your most recent series of works being shown at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, you seem to melt away the age-old rivalry between science and art. Where did this passion for science come from and how did you decide art was the best way to showcase that? (perhaps commenting a bit more on your current exhibition!)

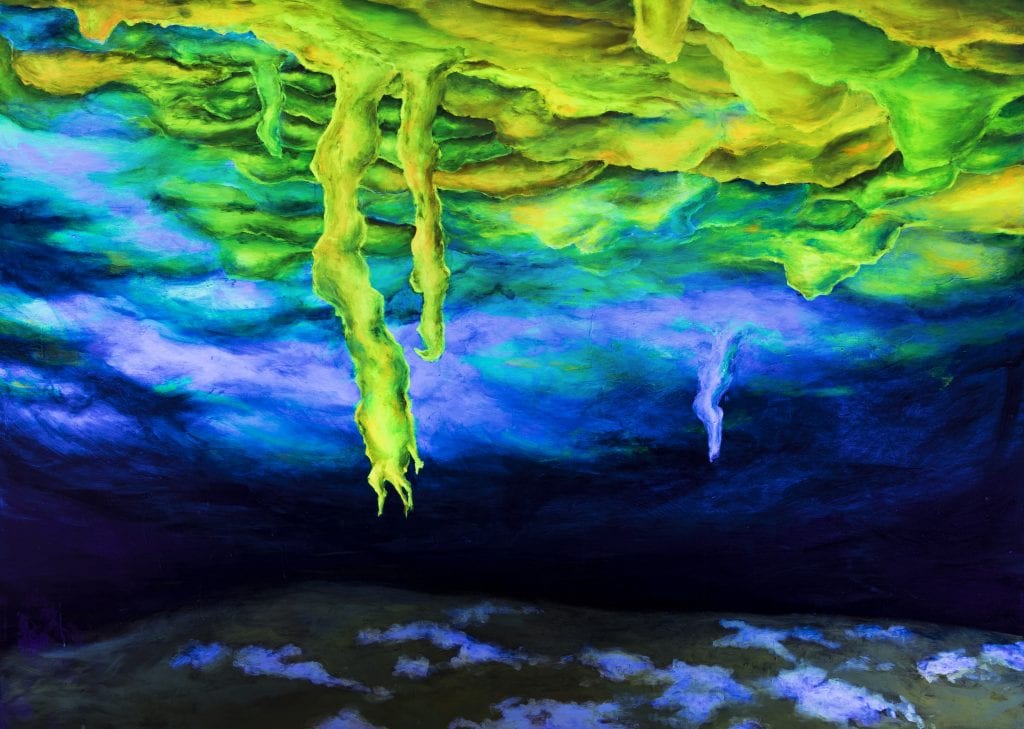

My passion for science followed my passion for art, rather than the other way around. The deep sea and the Antarctic initially represented the sublime — overwhelming, “pristine” environments, removed from the human world yet paradoxically susceptible to human impacts like global warming and resource extraction.

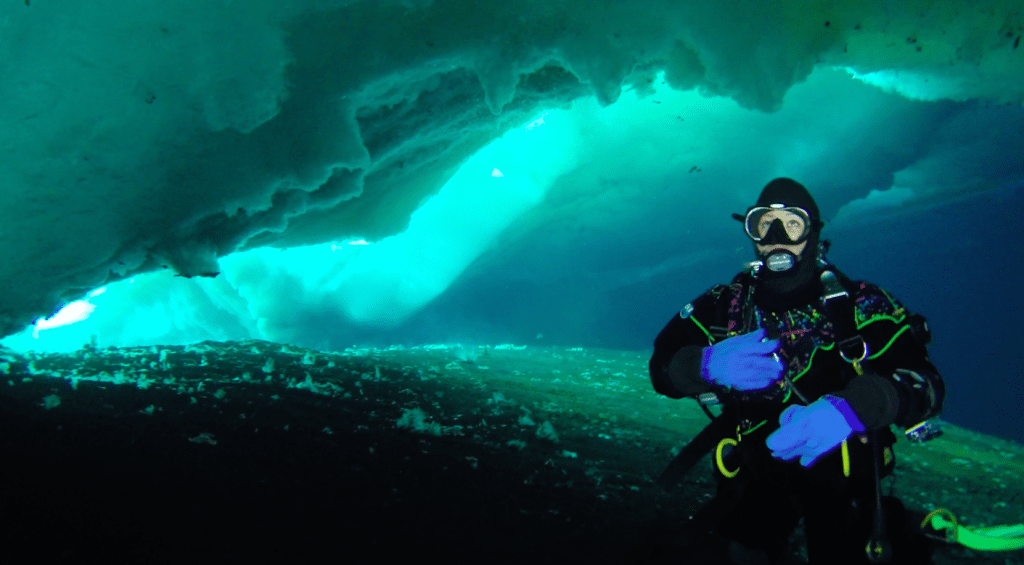

Because I am trained as an observational painter, I began working with scientists in order to see these largely-inaccessible places for myself and paint directly from life. The expeditions involve long periods of working together closely in isolated environments — aboard research vessels in the deep sea, diving in submarines, camping at remote sites in Antarctica. The more time I spent with scientists, the more the research itself emerged as a subject for my paintings.

The exhibition at Harvard is the culmination of my collaborations with scientists on six different deep-sea research expeditions, plus two residencies in Antarctica in which I spent many weeks camping with researchers and scuba diving beneath the sea ice. It’s interesting that you use the word rivalry, because I forget that art and science are often viewed as antithetical. I spend so much time now thinking about the ways in which they overlap. I’m used to showing in galleries, but the Harvard show provides such a

great context for this work because they have these amazing collections of artist-naturalists– the Blaschkas, Maria Merian, Audubon. I love putting my work in dialogue with the golden age of discovery, when art and science worked in tandem.

From where do you draw inspiration?

One parallel between art and science is that both fields are often asking these big existential questions, and finding answers in very specific, observed phenomena. The scientists I work with are usually studying a particular organism or ecosystem as a way to illuminate research questions that actually seem universally compelling. What are the origins of life? How can life exist on other planets? What do these creatures’ adaptations tell us about our future on this planet? And if the subject of that investigation is visually compelling as well, it becomes a muse that I return to again and again.

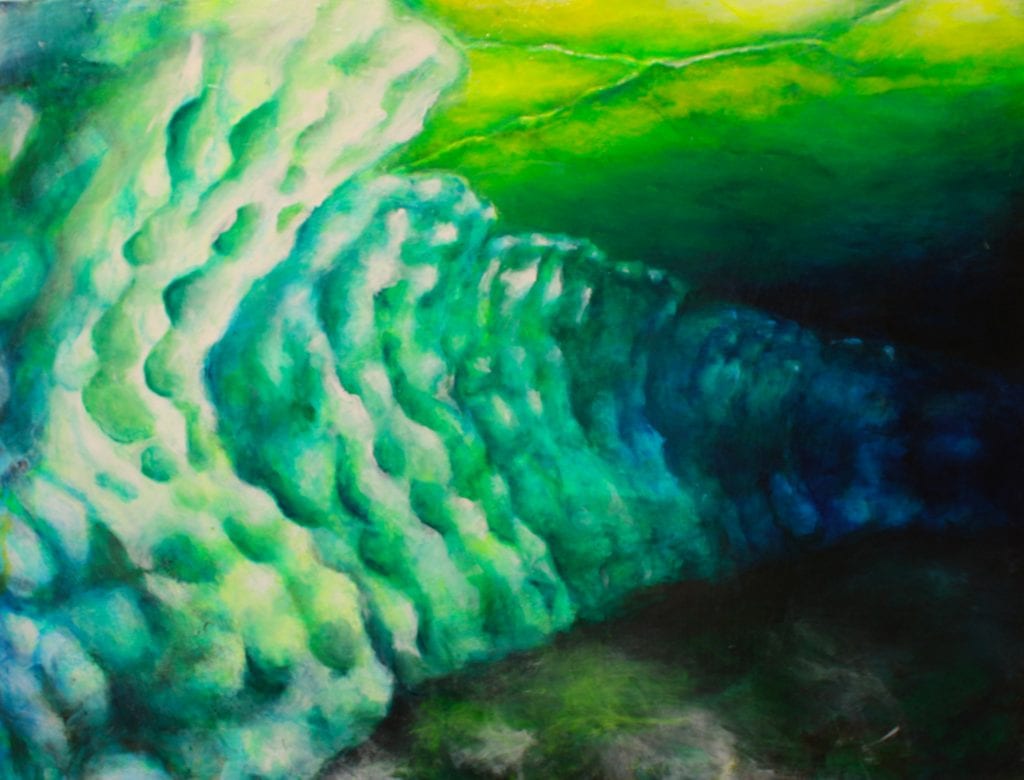

Cinder Cones Seep, McMaduro Sound (2018), Courtesy of Lily Simonson,

What medium do you use and how might that be important to your work overall?

I’m a painter and the medium of paint is really central to my practice. Many of my subjects from these unfamiliar worlds are so weird-looking that audiences think I’ve invented them. Then there’s this exciting moment of revelation, when the viewer realizes that this bizarre alien scene actually exists. That collapse of imagination and reality would not happen if I used a medium like photo or video, that have a promise of veracity.

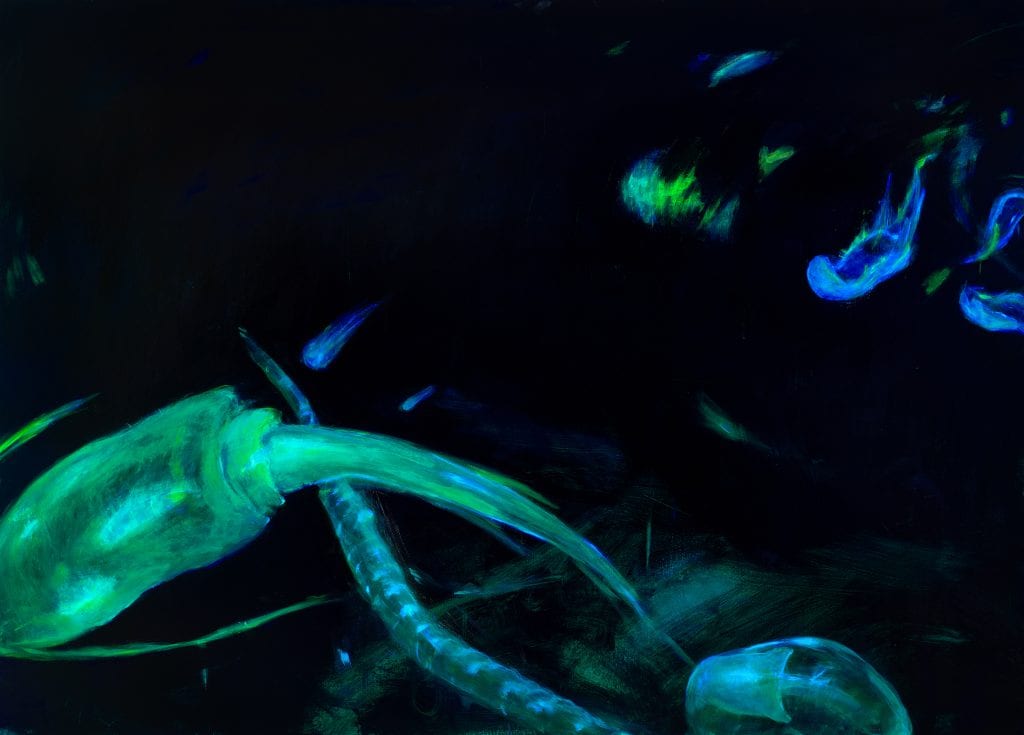

The Dream, Point Dume Seep No. 3 (2019), Courtesy of Lily Simonson,

Does your work reference any figures or movements from art history?

I paint using Renaissance glazing techniques that I have adapted for acrylics, because acrylics are much more practical for painting while on expeditions. I often appropriate compositions and titles from Renaissance and Baroque figure paintings. In this way, I invoke the human figure without actually painting the human figure. I have an aversion to the literal.

Submerged Glacier, Evans Wall, Antarctica (2016), Courtesy of Lily Simonson

What is your process like and how do you begin a work?

When I’m in the field or at sea I usually make paintings while looking directly at my subject. If it’s an organism that we’ve collected using the sub, I hold it in my hand as I’m painting and that way I can study its pigmentation, morphology, and movement. Those in situ paintings are complete works, but they also serve as studies for giant mural-scale paintings that I make back in my studio, where I have more space and time to paint. My process is very labor intensive and I spend about two years developing each body of work.

Expedition Shot of Lily Simonson scuba diving in the Antarctic Ocean

Have you always painted in the style your work currently inhabits?

I have always used lots of thin luminous glazes to create outsize atmospheric compositions. But my paintings have gotten increasingly psychedelic. After grad school I started using fluorescent pigments that glow in black light. I love referencing that 1960s aesthetic because my subjects seem like trippy hallucinations already. For example, the sea ice in Antarctica is white on top, but microalgae grows inside it and makes it glow underneath with crazy colors–neon green, vibrant turquoise, gold.

Installation View, Courtesy of Lily Simonson, Pteropods Under Ice

You also go on expeditions with scientists all over the world. What is the craziest story you could share in pursuit of your art?

The moment I saw images of the unique environment under the sea ice in Antarctica’s Ross Sea, I realised that I had to paint it, and therefore had to see it for myself. But you can’t just go there, you can only access that site through the National Science Foundation United States Antarctic Program, which mostly funds scientific research, but awards a research station residency to one artist or writer each year. Most grantees stay on land though! There have been more astronauts than Antarctic divers. The water is -2° celsius, you can only access it by scuba diving through a small hole in the ice, and if anything goes wrong you can’t just go to the surface because there is a six-foot-thick ceiling of ice overhead. It’s the riskiest diving on the planet and when I decided I needed to go there, I had no scuba diving experience. But I spent the next year learning to dive and spending every weekend underwater just so that I could apply to the Antarctic residency with a proposal that centered on diving under the ice. I had done about 100 dives by the time I got there, but by scientific diving standards that’s not a lot, so it was still pretty crazy. I thought maybe I’d get to dive a couple times, but I ended up diving every day for a month and it was the most transformative, mind-bending experience of my life. It simply cannot be captured in video or photos. The water is ten times more clear than anywhere else on the planet so it feels like you are suspended in the air rather than swimming. You’re surrounded by the weirdest creatures. The sea ice is the most vibrant gradient of colors and textures that you can imagine.

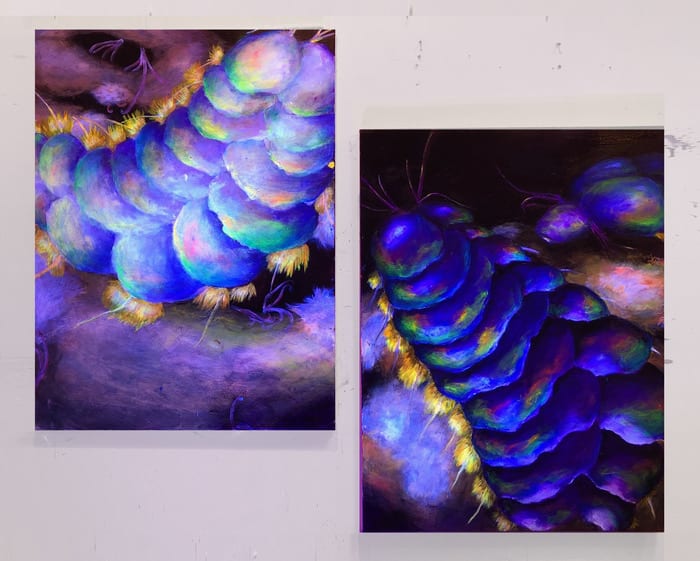

Penelope Diptych, Scaleworm Extravaganza (2019), Courtesy of Lily Simonson

What do you have planned post-pandemic?

As I mentioned at the start of the interview, the current civil rights movement has made me want to confront white supremacy more directly in my work. Much of my art addresses climate change, which disproportionately impacts developing nations and economically disadvantaged Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian communities within the US. But for the most part, my personal activism with regard to social justice has been separate from my practice. So right now I’m thinking about how my work can more directly merge the two, or if it’s even my place to try.

Lily Simonson painting aboard the Research Vessel Atlantis on an Expedition with the Girguis Lab to the East Pacific Rise

At the end of every interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

I’ve got two for you! Friends from grad school days at UCLA. Brenna Youngblood merges painting, photography, collage, and sculpture in the most distinctive way. I’m really excited to see her next project, which will be a public art installation in LA, on Crenshaw and Slauson. Vishal Jugdeo is another brilliant artist who became known for his video installations. For the past few years, has been working on a longer film with a queer activist in India, Vqueeram Aditya Sahai. I have loved seeing that project evolve.