Jack Kohler Byers’ art defies conventions of the traditional art scene. Self-trained, Byer’s practice is innately personal and cultivated from a very young age. His explorations into lettering are inspired by modern masters such as Picasso and find home on a vast range of surfaces. Byer’s lives and works in Boston, MA.

Tell us a little bit about yourself. Where are you from originally and what was your experience with art growing up?

My name is Jack Kohler Byers, I was born and raised in Cazenovia, a small town just outside of Syracuse, New York. I grew up playing with Legos instead of video games and action figures, and from a young age both of my parents encouraged me to create instead of consume.

Museums, not galleries, were a typical feature of any family trip. This rooted my understanding of art in creativity instead of commerce and taught me that art wasn’t defined by the walls of a gallery, but instead by the mind of the viewer and context of the piece. Visiting Syracuse as a kid I found myself drawn to the features of a fading industrial landscape, especially the remnants of signs painted on buildings. These fragmented messages activated my imagination to speculate about the day they were freshly painted, who painted them, and the different events that led to their decay. These century-old letters formed a dynamic contrast with more contemporary letters being painted around the city by its younger occupants.

You live and work in Boston, MA. What is the art scene like?

It’s impossible to compartmentalize or sum up with one word, and I think an artist’s experience with it depends on age, social status and the type of work they produce.

To many, the art world in Boston seems governed by conservatism and tradition, with little acceptance for anything produced outside of a handful of styles pushed by a small group of hometown heroes that have gotten shine on a national or international level. This is a direct product of Boston’s traditionalist view of art as being separated from day to day life. There’s not a lot of room for an emerging artist to feel legitimate because of the city’s 9-5 culture. You know–if you’re moonlighting in a restaurant to pay rent and making art outside of that, it can be hard here to feel like you’re doing little more than tread water.

Underneath all that though, there is a burgeoning art community filled with originality and intensely creative people putting in serious work that’s beginning to redefine the average Bostonian’s interaction with art. The members of that community find themselves in a unique position given Boston’s status as an international city. More and more I find it advantageous to work in a place that refuses to accept you unless you’ve found success elsewhere. That provides the impetus to branch out and collaborate in places outside of Boston and gives you the clout to then choose which part of the scene you can work to help elevate.

What artists, living and dead, most inspire your work?

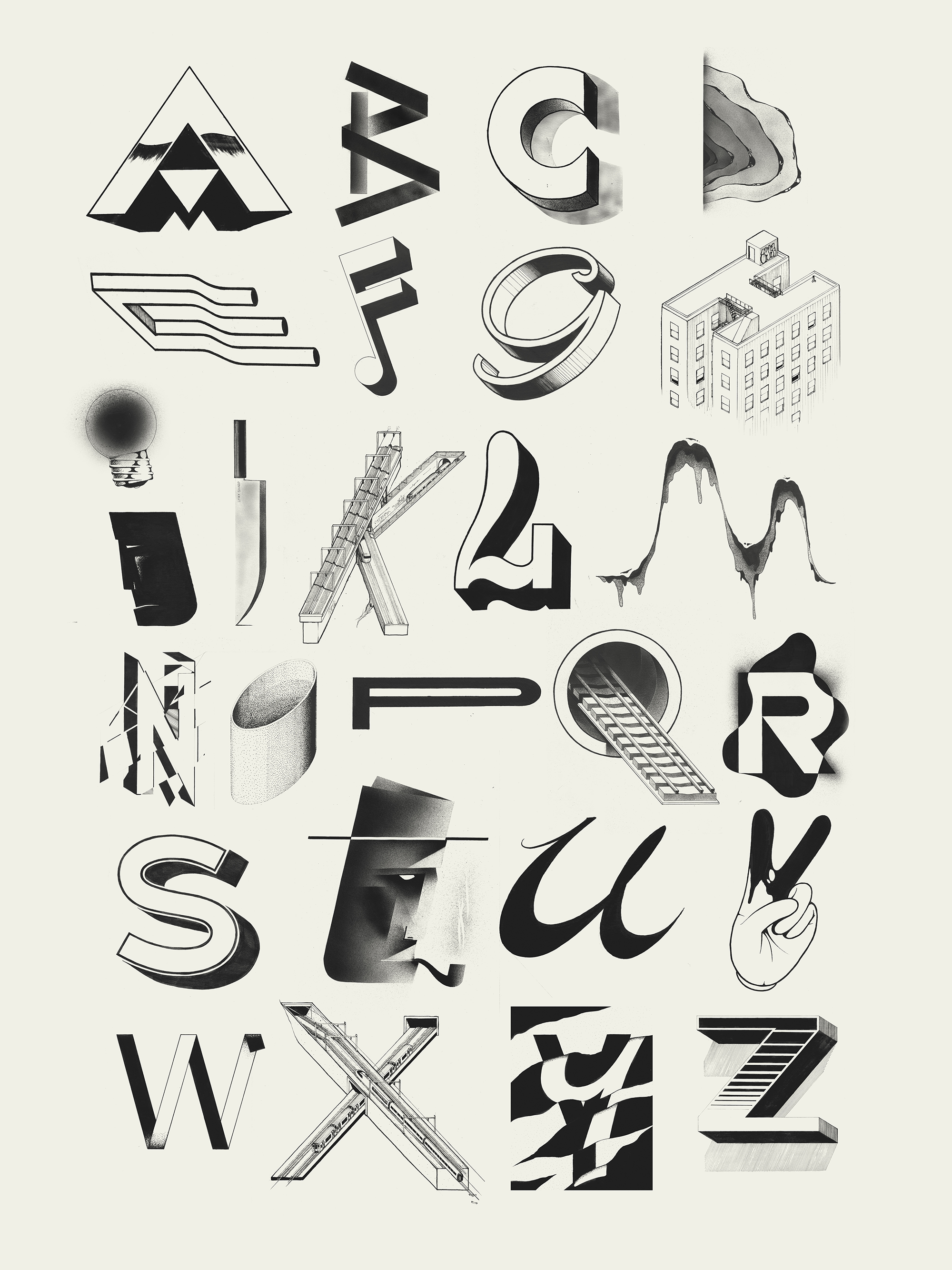

Most of my idols are dead. Probably my biggest inspiration is the work of the mid-century renaissance man, Gyorgy Kepes. Reading his book on the origins and development of modernism in art and design, “Language Of Vision” was a watershed moment for me. That book introduced me to the work of A.M. Cassandre, El Lissitzky, and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, all huge influences. Picasso’s work also informs mine in a big way, notably his mural Guernica. I remember reading that underneath Picasso’s cubist painting “Girl with a Mandolin” is a realistic sketch of a girl. When I found out that he reverse-engineered cubism from realism it was a jumping off point for a ton of exploration.

Contemporary artists that inspire me are too numerous thanks to the magic of Instagram. There are a few that have been pretty pivotal in shaping my taste. The Iranian painter Mehdi Ghadyanloo is inspiring to me on many levels. He painted his first mural on US soil in Boston in 2016. He and his family’s visas were revoked at the 11th hour before he was to start work, but finally a few weeks later he was able to get a visa for just himself. He then crushed it, making one of the most memorable murals in the city, a good reminder that there’s literally no excuse to give up.

I try to limit the amount of contemporary lettering art and illustration I look at in order to avoid falling prey to trends, but ROIDS, Horphe, Will Barras, and Karolis Strautniekas are all favorites.

How has your art practice changed throughout the year?

I don’t have the benefit of a formal artistic training, everything I learned was by reading, learning lessons, and picking up wisdom from others. When I first started getting serious about making artwork, I put a ton of emphasis on making something finished and perfect each time. This led to occasional successes, but much more frequent periods of frustration and burnout. As time goes on, I’ve learned how to walk away and let time work on a piece for a bit. Instead of tearing up a drawing that wasn’t coming out the way I want, I now roll it up and stick it in a tube. Months later I come back to it and have none of the prior frustration, and it becomes a kind of game to resolve the chaos into something I like.

Do you have a favorite medium to work in?

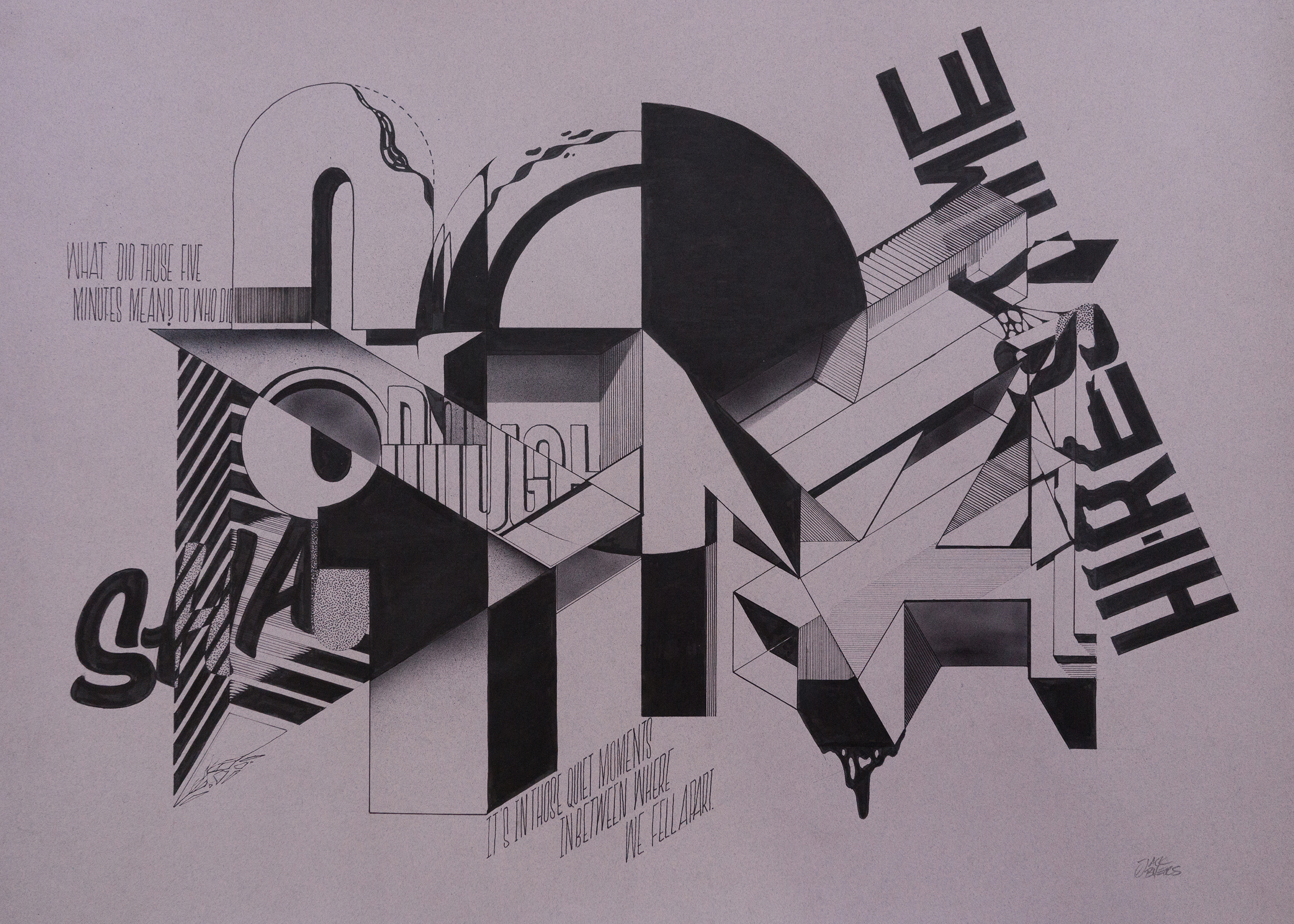

My go-to is ink on paper. When I was younger and trying to teach myself graffiti letters, I was told that color should always come second. Make a piece work in black and white by balancing those two forces, then learn how to do it with color. Ink was the natural mode of expression because of how binary it is; you’ve got either ink, or paper, and there’s no command+z.

I also really enjoy painting murals, and when I do, I use colors, but always in a way that accentuates the form. For a long time, I spurned doing digital work, but I’ve come around to that as well. Designing digitally can be a crutch if it’s exploited, but when used in tandem with handwork it is a great way to speed up process and experiment with color more efficiently. I do maintain a fairly well-defined boundary between my use of digital and analog tools. For the most part, my personal artwork is all done by hand, and commercial illustration work is finished digitally.

How does the experience of working directly on walls vs. on a more contain surface, such as paper, differ for you?

The differences of the two mediums totally shifts my process for working with each one. Because I’m typically using paint, working on walls is an additive process for me. I can apply and subtract layers and therefore usually go in with less of a plan. I work in a similar way to an oceanic tide, bringing broad forms in, paring them back to reveal details, then repeating.

Smaller surfaces on the other hand are typically done with ink, a subtractive process. Sometimes it’s like walking a beach after the tide goes out. I work more slowly and locally than in my wall work, moving from section to section while gradually sharpening broad forms.

Your work contains a lot of imagery of trains. Where does this interest come from?

Trains are dope! Going back to my fascination with a hidden history when I was younger, there was a red caboose sitting on a disconnected piece of railroad track near where I grew up. The tracks had been long since ripped out, but it made me constantly think about a different place. When I got older, I spent some time in freight rail yards at night. Being surrounded by massive pieces of metal that are here today and thousands of miles away next week was a very humbling experience.

Now, living in a city, trains allow me to get around without having to own a car. The occurrence of trains in my work now has a lot to do with contemplating why Americans are so wrapped up with owning cars. What used to be a bastion of American Independence is now a big hunk of metal and plastic that depreciates wildly and keeps the average person idling in traffic for 42 hours per year.

From where does the visual language that you produce originate?

It has its roots throughout my life, but really came together in 2014. I was disillusioned with trying to perfect a hand-lettering style because doing so made me feel like a cover band. I didn’t like how lettering art had to have a distinct message and seeing the repetition of the same hollow maxims only furthered this dissatisfaction. One night I made a drawing meant as a joke, spelling out a word by haphazardly arranging boring sans-serif lettering and focusing less on the layout of the letters and more on the way they interacted. When I finished, I sent it to friends, asking if they could read it. None of them read the word I wrote, but instead were seeing words or phrases that kind of fit their personality. I dove as far into this idea as I could. I looked at how modernist painters from the 20th century broke down the image into its bare fundamentals and applied the same thought to letters. Since then I’ve been exploring how to create images that have just enough information to keep your attention, but not so much that you’re able to glean a singular meaning. Hence the term visual speedbumps.

What’s next for you? What has you excited right now?

I’m looking forward to taking a break from paper and pen and learning how to apply my visual language to a new, larger media. While I work out the inevitable kinks of that transition, I will be releasing some prints and working on an exciting client project that I can’t spill the beans about quite yet. Let’s just say it’s been a dream of mine since high school. I’m also working on doing weekly illustrations to accompany beats made by my friend Edot. He’s a sick producer, and I’m pretty particular with what Hip Hop I’m into.

The thing that gets me most excited is seeing my friends push the envelope and continue to pursue their crafts. The single biggest motivator for me is watching friends get bigger opportunities because that keeps me on my toes to go after more ambitious things myself.

At the end of every interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

Without question: my friend, mentor, and collaborator David Buckley Borden. David constantly pushes me by asking the difficult questions that need to be asked in order to grow. His work is very important at this exact moment in history due to its ability to lend a relatable side to complex scientific issues using art and design. All of this is accomplished elegantly with his sense of humor, impeccable eye for design, and a strict no excuses policy.