Ladies Choice is an ongoing series highlighting female artists working in New York City and beyond. This series honors the power and ingenuity of women in the arts. Women have traditionally received much less exposure and recognition in the art industry. In their support of one another, these women stand as a testament to furthering the careers of female artists.

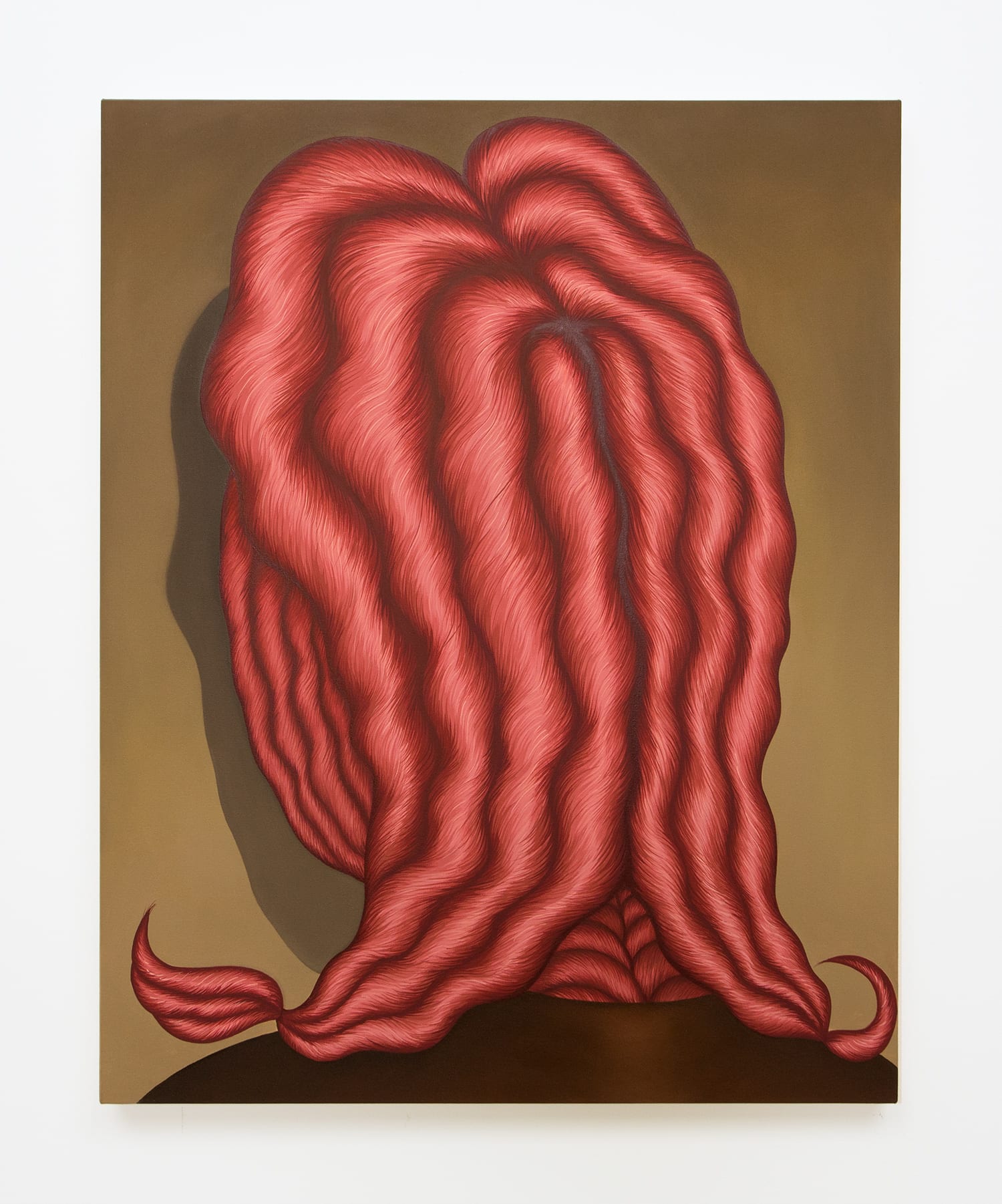

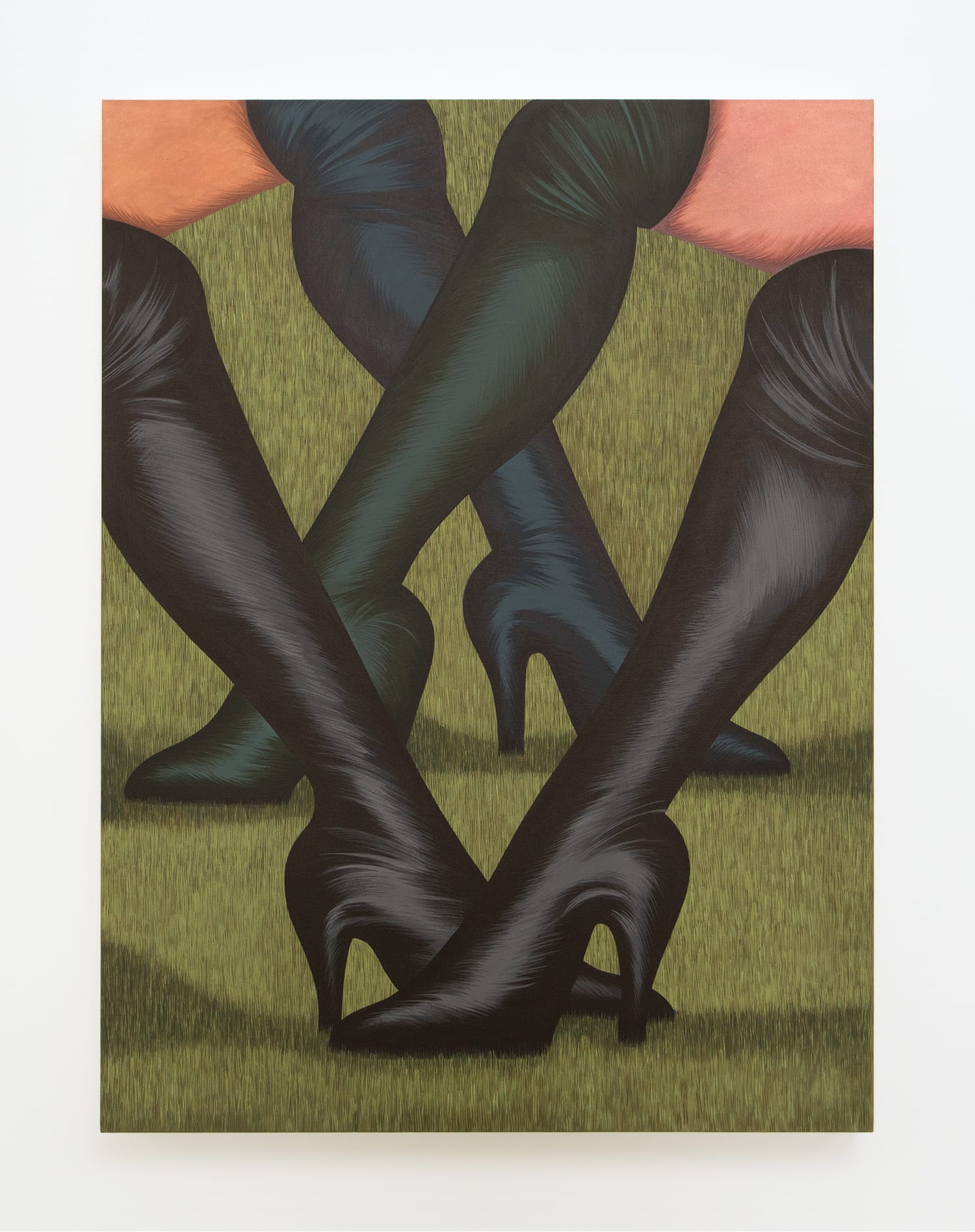

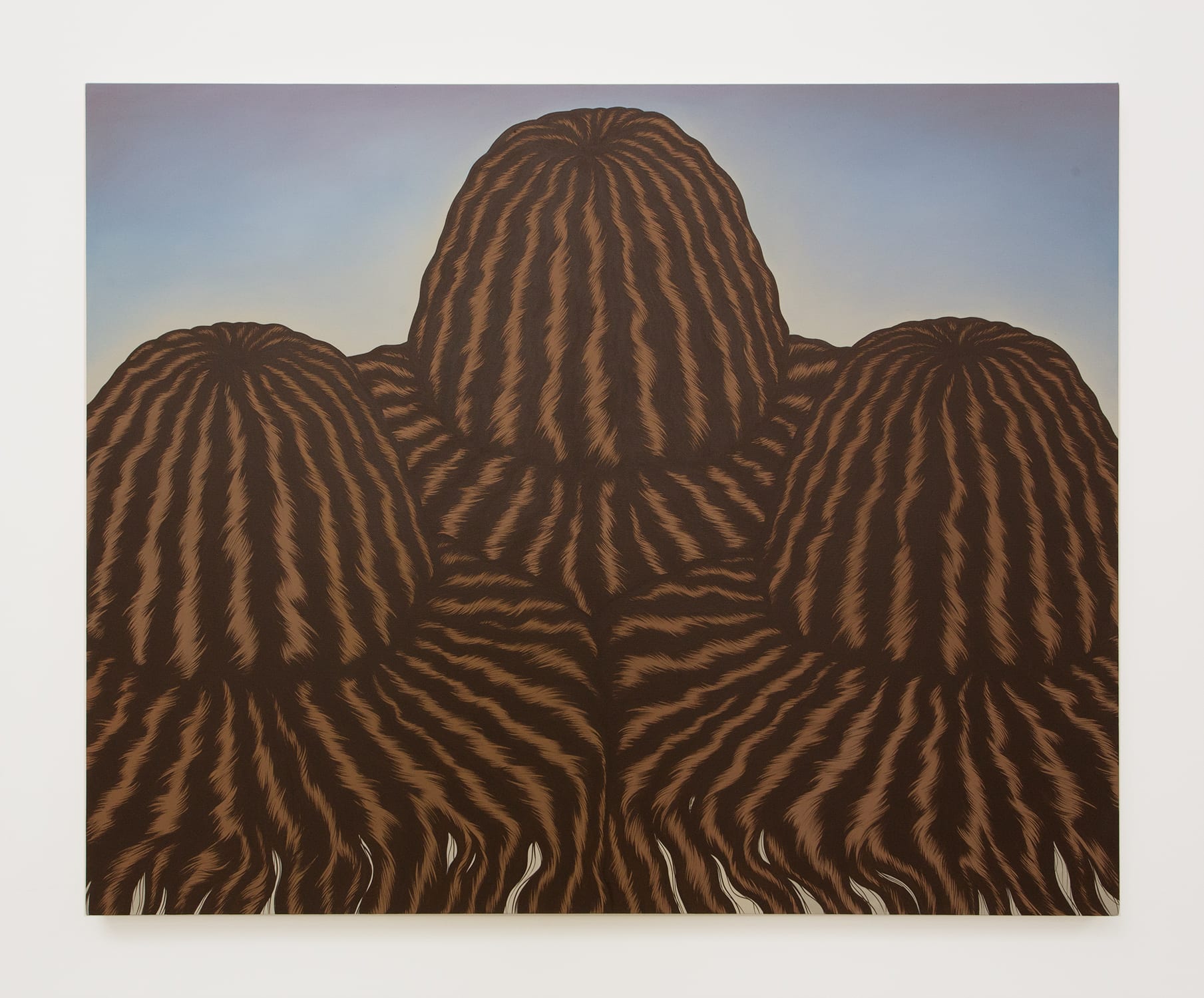

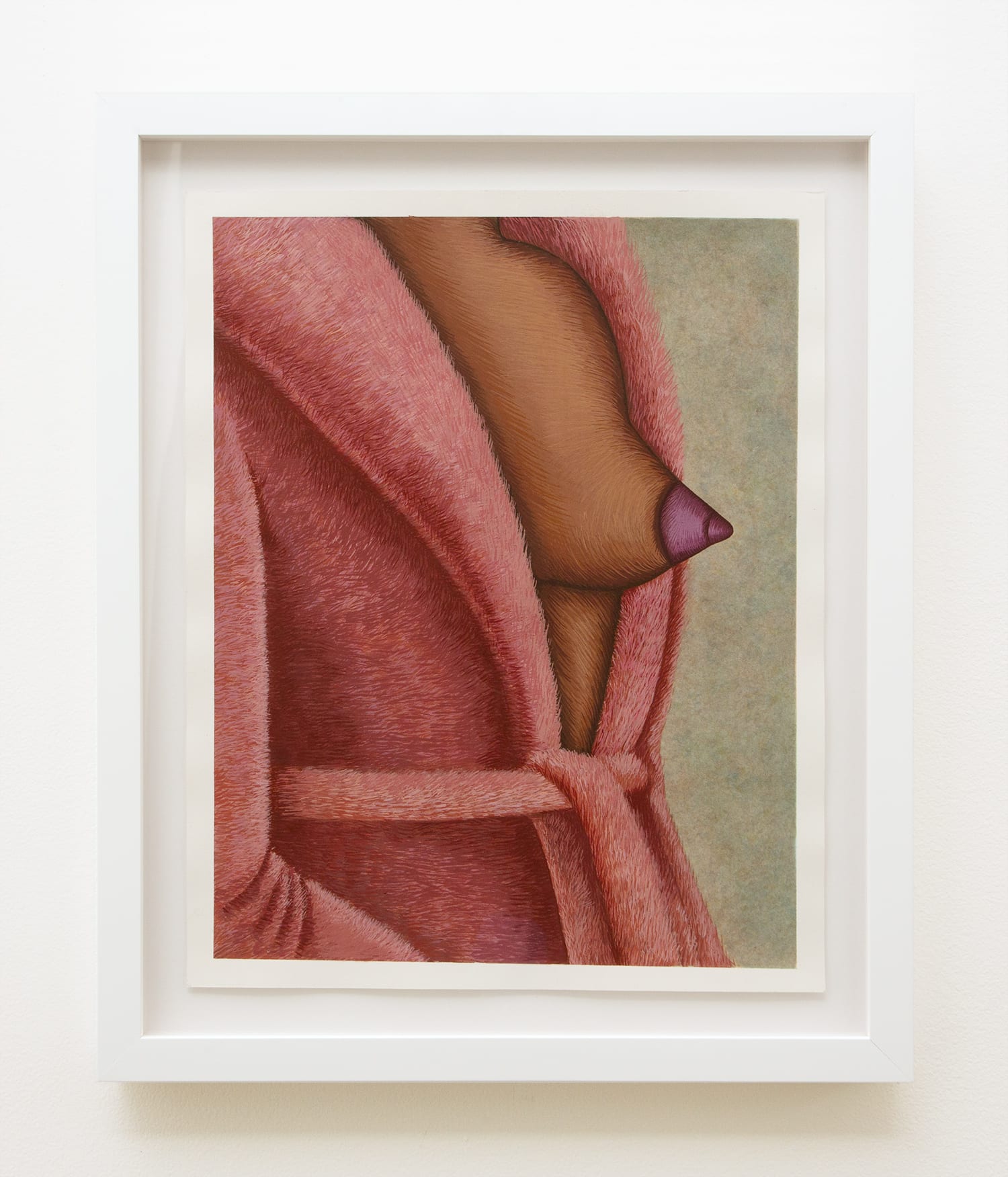

Julie Curtiss is a French artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Her paintings evoke both humor and darkness, familiarity and strangeness. They are vividly colorful and playful, yet contain underlying psychological elements, contrasting the feeling of being comforted with the surreal. Julie is represented by Various Small Fires Gallery In Los Angeles where her show Altered States is currently on view.

You are part of a young generation of female artists hustling and gaining recognition in NYC. What does being a part of a strong female community mean for you?

It means so much to me, and it has been truly inspiring to see so many female friends grow as artists and become visible. I feel lucky to witness and participate in this very special moment in the New York art scene.

Which female artists, living or dead, inspire you most?

I identify and enjoy so many female artists, but I would say the works of a few women have considerably informed my practice both formally and conceptually: Louise Bourgeois, Christina Ramberg, Nicole Eisenman, Elena Ferrante (a writer), Ellen Berkenblit, and Dorothea Tanning’s sculptures.

Have you experienced firsthand the underrepresentation of female artists in the art industry?

I can’t remember a clear instance when I was underrepresented because of my gender.

Have you noticed a change in opportunities available for female artists since you first entered the art world?

Personally, a change that affected my career was the recent shift of focus from abstract to figurative painting. In addition to that, the elections and the sexual harassment scandals triggered a change in the way society regards women. The fact that I paint about womanhood on a psychological and cultural level was very timely and opportune. I can see many similar cases around me.

If you could change one thing about the current landscape for working female artists what would it be?

I think there isn’t a sufficient family support system in the US. We desperately need a decent maternal/paternal leave in the workplace and affordable childcare. I am completely supportive of women who decide to become full-time moms. But too often having a child for women means scarifying their career.

Your works, both in Altered States, and elsewhere, mostly depict female subjects. Why is this?

My work is deeply personal, I think I am painting from my point of view about the woman’s psyche. However, my work has elements of masculinity also. For instance, my characters often have very masculine or aggressive traits such as strong hands, razor sharp nails.

Why were you initially drawn to marine imagery and 1980s science-fiction film that inspired these works?

I am interested in inter-species relationship: the way we project onto animals, how closely we interact with them – we pet them and we feed off them. They are a constant reminder that we are animals ourselves. Also, I am interested in how we relate to the most genetically remote animals, and therefore how we relate to the most alien part of ourselves. That’s why I am fond of marine creatures. Identifying to a cat or a monkey is easy. It is so much more destabilizing to feel sympathy for a lobster.

Your paintings are sexual but still retain a playful quality. Can you explain why you blur the lines between nature and reality with this cartoon-like, whimsical quality?

I love cartoon’s esthetic because behind it, there is a tradition of narration and storytelling. When I use this cartoon like imagery, I encourage viewers to make their own connections and elaborate on what’s outside the frame. The subconscious mind plays a big part in my work. Often, the language of dreams captures something archetypal. Similarly, cartoonists speak to people’s imagination with pictures that are simplified, reduced to their essence, easily digestible. This way they can convey an idea or an emotion more efficiently. I think many Chicago imagists understood this and used it in their work.

How has your French background as well as time spent in Paris influenced your practice?

Tremendously. In a way, you understand yourself better when you have lived in a foreign country. After being displaced for a while, you start perceiving when it’s your culture speaking or when it’s your nature. Some of my first encounters with art were in French museums. My first love with art was at Orsay, with the French sculptors, designers and painters of the 18th and 19th century. In a way I have this very classical background. I had absolutely zero contact with subculture for the longest time. There was a lot to digest when I first came to the US.

Can you describe your process? What does it for you to complete a painting from start to finish? How do you know when you are satisfied with the outcome of any one work?

My best ideas come when I take a stroll, observe things around me or in my waking hours. I also look at images on the phone or at the museum. I need to have an idea that strikes me and I then work on sketches before getting started on the canvas. Some paintings come easily, some resist and they become an obstinate battle. I will change the composition and colors over and over, then set them aside for a short or a long time. Eventually they come together. It’s pretty intuitive. Something is finished, not when I am satisfied, but when I can’t go any further.

In the works in Altered States you paint the same texture for hair as you do for other subjects, such as a lobster or watermelon. Why is this?

It’s something that I tried once because it was pleasurable for me to paint hair and then I was like, “Why not paint this other thing as if it was made out of hair,” and it continued like this. It’s a way of blurring boundaries between the inanimate and the living, between the internal and the external world. It’s also a way to appeal to the sense of touch, or to sensuality.

Let’s talk about your wig sculptures. You mentioned that it took some time to master the technique to make them sculptural enough to your liking. Can you please tell us a little about these sculptural works and how they relate to the paintings or drawings?

While visiting my studio, Esther and Sara from VSF gallery saw these hats I made years ago as a fun project, and they offered me a chance to make some new ones and show them for my solo show. It was an exciting chance for me to diversify and experiment. However, it took me a while to make them match my painting standards. It took years to develop my painting technique and I only had a couple months to figure how to make these sculptures. I think the hats reinforce the surrealist quality of my works. They are impossible objects are made tangible. Like I was saying earlier, I like to blur the lines because reality and fantasy.

At the end of every interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

One friend isn’t enough! Ok, I will say Genesis Belanger, because her ceramic sculptures have for me this perfect balance between craft and concept, depth and fun, realism and surrealism.