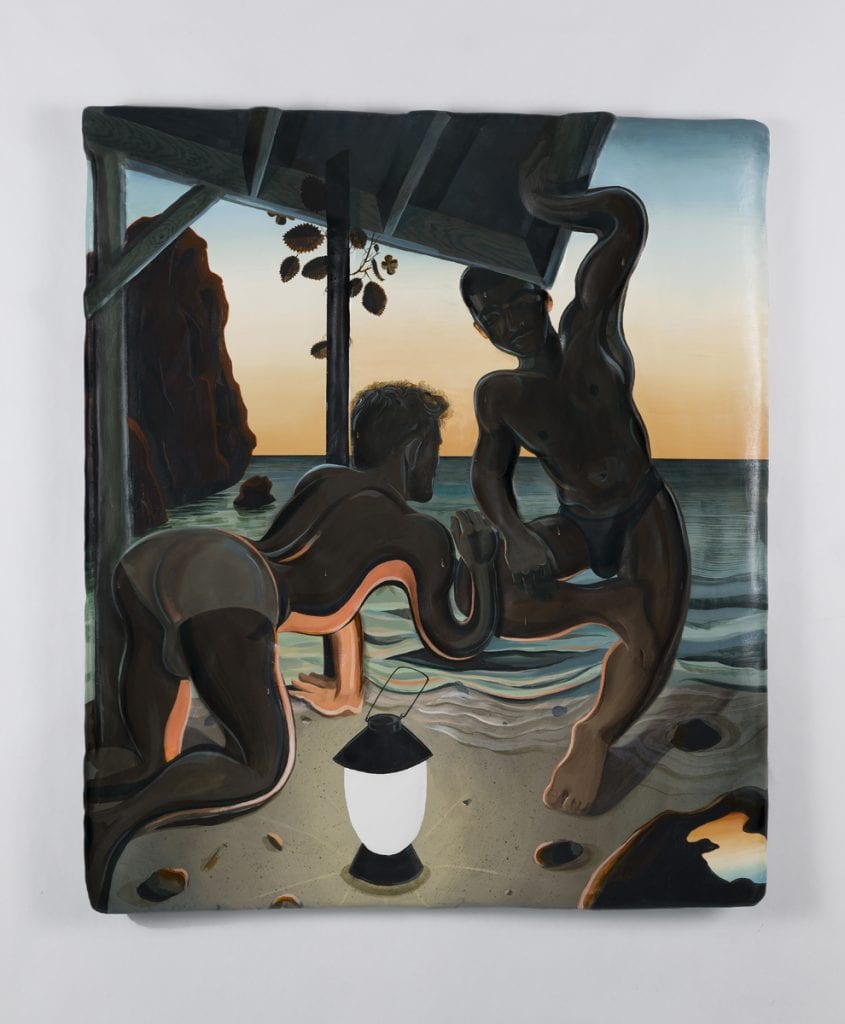

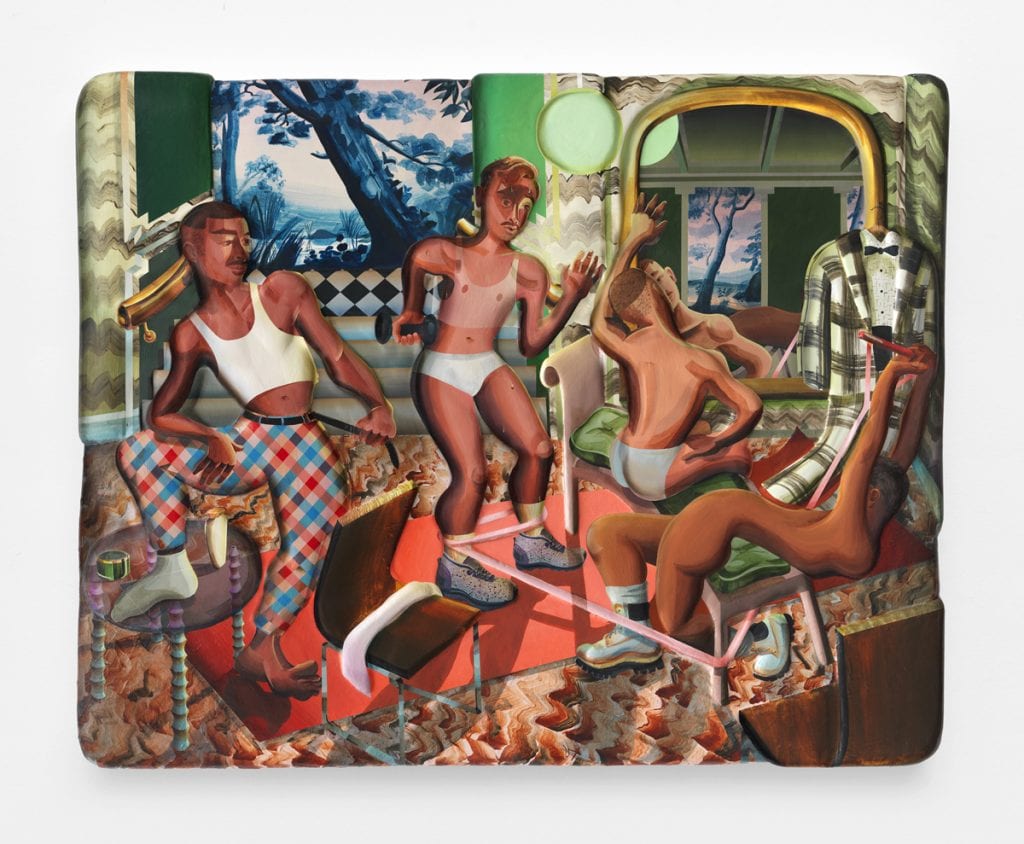

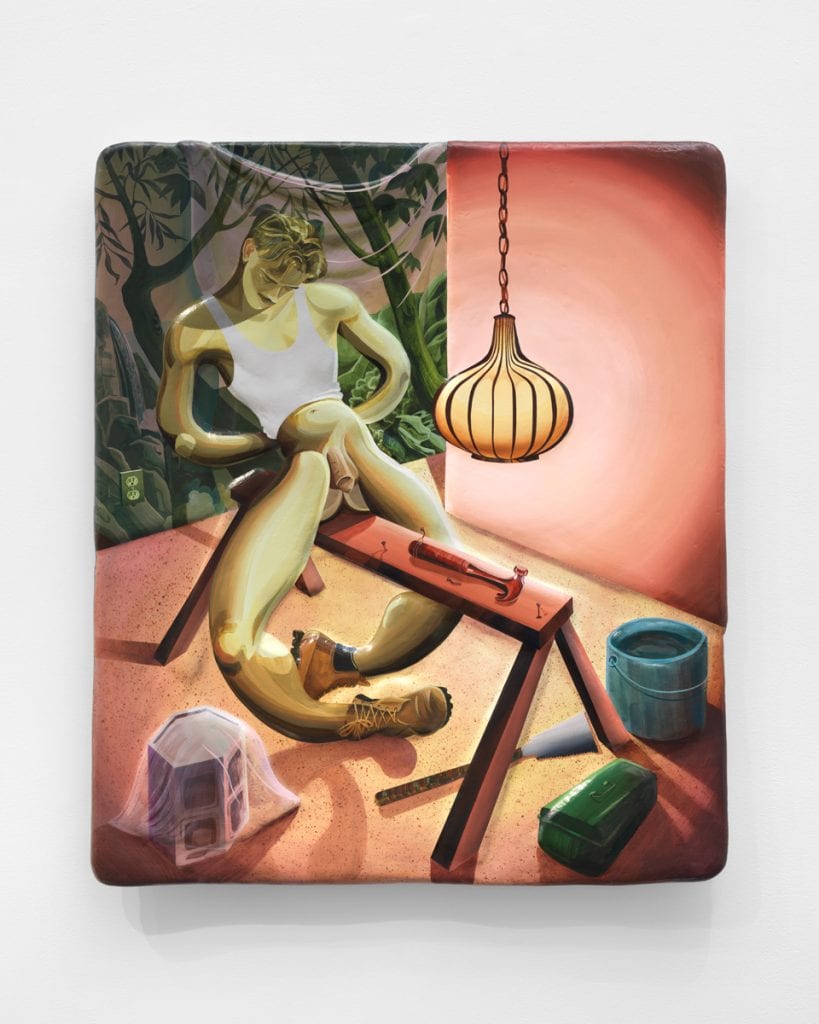

Kyle Vu-Dunn’s relief paintings defy categorical restraints, blurring the lines between sculpture and painting. Employing the idea that a painting does not have to be flat, Vu-Dunn carves sculptural elements into what otherwise would appear to be a two-dimensional surface. Vu-Dunn’s works can be read both as allegorical tales and as experiences the artist himself has encountered living as a queer man. He uses his work to celebrate an often-repressed male sensuality and create a world where men are allowed to display the full spectrum of emotions. In 2018, Vu-Dunn celebrated a landmark year in his career that is sure to only continue with his plans for this year. Here, we chat with Vu-Dunn about his unique style of creating and his growing success. Vu-Dunn lives and works in Queens, NY.

How has your work evolved since you first started creating?

My newest work is bigger and more populated than what I have made in the past. The last set of paintings was quite romantic and as such often had two figures. These days I am gravitating toward the lone figure or groups. The lone figure is somehow easier to understand as they are more integrated into their surroundings, while two figures always seem in relation to each other even if they are not explicitly interacting.

Your work is made in a very distinct way. Was there a breakthrough moment when you realized you could create work in this unique, painting-meets-sculpture sort of way?

It was not a breakthrough so much as a slow burn. I come from a sculpture background.

I had been using these materials for several years in different ways, but it finally seemed to click as shallow bas-relief panels. The limits of the panel’s edges made me focus more on the painting element, and over time it became dominant. I now sketch constantly as well and plan on showing some graphite works on paper later this year along with the reliefs.

What stories are you trying to tell with you work?

I want to embrace the eroticism of my subjects while interjecting emotions not usually associated with the gay male body – romance, doubt, humor, solitude, melancholy. A lot of queer visual art is relentlessly sexual without content beyond sexuality. I am trying to walk the line between saying yes, sex and pleasure are good! and great! But that doesn’t have to come at the expense of story.

The work from my most recent solo show was largely romantic stories. To shake things up for myself, the new pieces I’m working on are more ominous. The Window from that show is indicative of the direction I am going in. I just finished what I like to think of as that painting’s older brother. In this iteration, it is not a still life but has a lone figure who is not to scale with the room he is in, to claustrophobic effect. I am also experimenting with moving the “camera” around more, a cinematic trick from old horror movies to destabilize the viewer.

Who are the characters in your paintings?

I start with photos of myself or my husband, but this is mostly for convenience’s sake. My older work felt more autobiographical, but these days I find that our identities don’t matter. I often turn the figure’s face away to avoid straight portraiture.

How do you come up with the scenes that play out in your work?

I compulsively collect images from all over—pictures from social media, Japanese erotic shunga prints, film stills, fashion photography, interior design, etc. Sometimes the mise-en-scène dictates the figures and sometimes I start with the figure and create the composition around them. My most recent painting is a screenshot of an Instagram story of someone going from dancing to face-planting on New Year’s Eve.

There is often one emotion or narrative thrust that creates the framework for the paintings. I like to pick a certain activity or hobby—replete with its set of props and implements—and then insert my characters into them. For example, Home Reno (2018) started with the simple idea of a kind of gay parody of Tim Allen’s Tool Time character, made into this erotic fantasy. The props associated with this—saw, hammer, paint bucket—tell you immediately what is going on in the scene and are an entry point to the subject.

This signifier prop approach is something I learned from both Bob Mizer beefcake photography (for example, a boy wrapped in cellophane in front of a Christmas tree) and also Dana Schutz’s early paintings that centered on a simple hypothetical (for example, Gravity Fanatic). While it’s not necessarily in “good taste” I have always loved Alphonse Mucha as well; besides being a master draughtsman, his theater posters of Sarah Bernhardt convey both emotion and the play’s story with succinctly chosen props and dress. There’s a campiness to it that I love.

2018 ended in a big way for you with a solo show at Thierry Goldberg Gallery and a feature in Artforum. What do you have on deck for this year?

The Artforum feature was very exciting and a big professional milestone for me. The work made for it was in my show Always at Thierry Goldberg, so the two projects were intertwined.

So far in 2019, I will be in a group show at Maria Bernheim Gallery (Zurich, March), The Dallas Art Fair with Thierry Goldberg (April), The Armory and Frieze fairs with The Breeder Gallery (Athens, Greece), and a solo show at M+B Gallery (Los Angeles, October).

At the end of every interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?