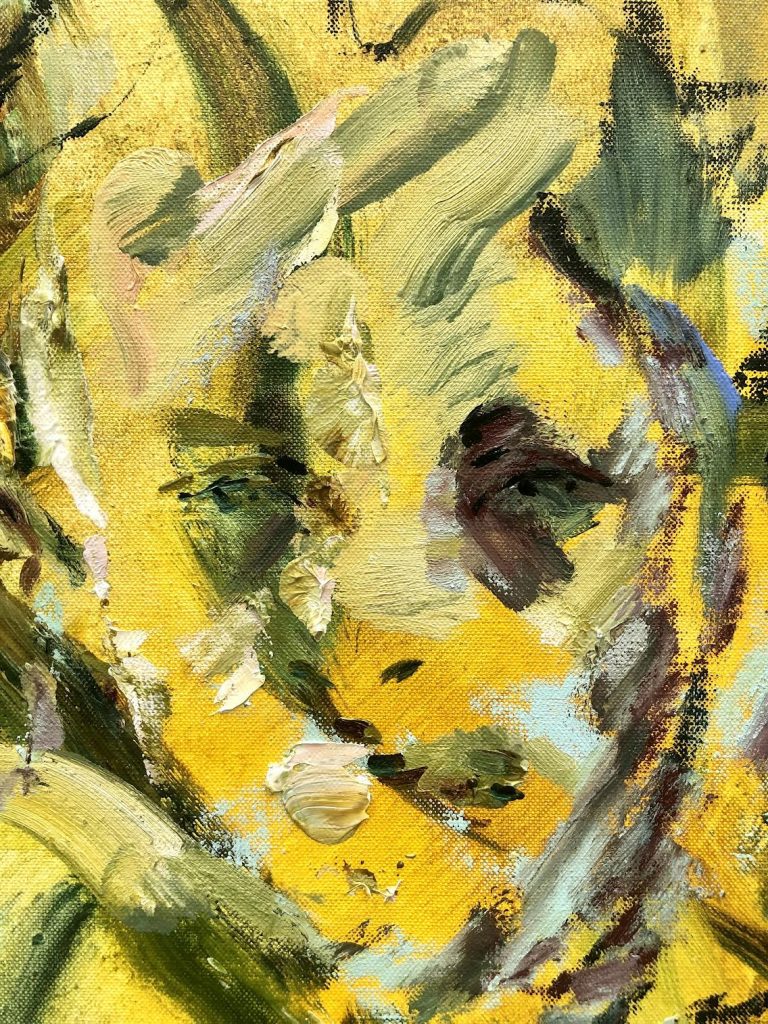

Kylie Manning is a Brooklyn-based artist making work that reveals a hybrid of abstract and figurative painting. With a focus on light and brushwork, Manning creates dark yet humorous oil paintings that entice the viewer to open dialogue about femininity and surrealism.

Tell us a little bit about yourself. Where are you from originally and when did art first enter your life?

I was raised between Alaska and Mexico by two art teachers who spent their lives fighting for arts education. I don’t remember art entering my life because it was always a constant. Sitting in on my father’s art classes as a young child and drawing the nude was a regular evening, and art permeated our home and lifestyle. Early in my art career, in order to have time to commit to my practice, I would return home to commercial fish every summer. This work formed the way I relate to scale and a need for bravery and weather in each work. At a certain point I had sustained enough injuries and had too many close calls on the water (most people I knew were missing, at the very least, a few fingers) and I couldn’t rationalize risking my painting hand any longer – no matter how lucrative a fishing season could be. However, this time was deeply formative in my relationship to the environment.

Have you always painted in the style your work currently inhabits?

A friend from grad school recently passed by the studio and mentioned that she was so happy that no matter where she came across it, she could still always tell when a work was mine. So, I believe yes, but at the same time I of course hope it is growing and shifting. People have often described the work’s ‘style’ as the oscillation between abstraction and figuration, but that is actually the by-product of a lifelong interest in something visually related to what the writer Renée Ashley describes: “I’m drawn to what flutters nebulously at the edges, at the corner of my eye — just outside my certain sight. I want to share in what I am routinely denied or only suspect exists. I long for a glimpse of what is beginning to occur.” This act of shifting is the rhumb line for what has been consistent in my work since I was a child. There is an element of training and researching that is always superseded by joy and excitement. The moment of superseding is where the work shatters itself and really starts getting activated.

What’s a day in the studio like for you?

I’m usually in the studio 6 days a week from 12-9 pm, but if a work is really happening, I’ll stay till 10 or 11 a few times a week. I am very fortunate in that I share a studio with two artists I love – if they are there we will catch up with a coffee or a glass of wine and chat about the works at hand or exhibitions we have recently seen. If they are not, I usually stare at the pieces for at least a few hours – mentally building up the momentum and decisions I believe required for a few marks. I’ll warm up with stretching linens or grinding some pigments, maybe sizing some works, then really get cracking in the late afternoon/early evening.

What’s next for you?

Anonymous gallery is bringing some works to NADA in Miami that I am so excited to share with everyone, and there are some incredible projects in 2022, but unfortunately, I can’t share them yet. More to come!

From where do you draw inspiration?

Many of the initial thoughts are based on a temperature, a specific time of day, a specific latitude, what knot is the wind and how damp is the air. This is where the upbringing comes into focus. If I can capture a very specific climate, then the viewer can remember when they were in a similar space. If that origin is successful, I can often be freer with the following marks, layers, and narrative implications. The original environment sets into motion all of the future color choices. It decides what type of world the piece will exist in and how/when it will fold into itself. The recent Ruth Asawa exhibition was quite an inspiration, I relate so much to her way of making and being. Her relationship to the eye and the hand as a lifelong exploration is something I hold in high esteem. Though the outcomes are very different, both of our works try to glide through a variety of implications and connotations. The more I learn about her, the more I am inspired.

Has your work always taken on the style it currently embodies?

“Kylie Manning makes it easy to believe that she makes straightforward paintings. They present themselves like gestural scenes, are usually frontal, and depict groups of people set against or within a landscape. She paints with lyrical deft and the assertive confidence of an artist who knows what she’s doing. You trust her rendering, the building of atmosphere and temperature. And then, while studying the bloom of pink and acidic olive into ochres and deeper greens, the status of the artworks as scenes becomes uncertain as the conditions of narrative also melt: Who are these people, and how do they know each other? Where did they come from? Why are they looking at me? Are they people at all? What are they doing in that river? By design, these questions have no answer. Contemporary U.S. figuration places a high premium on the creation of consistent worlds and how bodies communicate narrative. Paint is the tool which makes and maintains these worlds. For Manning, paint is a medium of inconsistency. If a line can be used to describe the parameter of a body which would not exist otherwise, it can also break the continuity of a painted picture. A line can misbehave: it can unstick itself from its place in proper perspective; can contour the wrong parts of the story; remind us that images are not a given in art. If eyes can gaze back at a viewer, so can stains. If brushwork can evoke water, grasses and mists, it can also do a dance led less by grace than excitement, unsettling a painting laterally, in ripples. If gesture is a language, so are expressions and emoticons.” – Gaby Collins-Fernandez

What source material do you base your work off of?

Family photos from the 80’s are often my starting place. They usually consist of large groups of people wrangled like wet cats to document a moment. As the compositions in my works often require large groups of figurative implications it is a natural and personal starting place. Compositions usually begin with a very loose visual conversation with those photos, and then blossoms into whatever direction the piece needs to go.

Does your work reference any Art Historical movements?

The people I think the most about don’t often pop up in a direct reference. I think a great deal about woman, queer artists, and underrepresented voices who carved the way for us. I recently got a book of Elaine De Kooning’s selected writings, which basically invented the press release. I’m interested in the cocoon Joseph and Annie Albers created at Black Mountain College and am directly affected by the New Leipzig school having been sent to paint in Leipzig down the hall from the likes of Neo Rauch and Tilos Baumgartel during formative years. For the works to successfully undermine what people think of as a masterpiece, and who can create one, they have to be masterful. So, I’m constantly looking a great deal and will often give a direct nod to someone like Franz Halls or Edvard Munch.

What is your process like? How do you begin a work?

I usually begin a body of work as a sort of family. Spending time stretching the work, sizing with rabbit skin glue, spreading oil ground by knife and sanding down multiple layers, I build a relationship to each individual piece before color starts. This process creates a path to being close to a work and build a joined spirit. I’m acutely aware of the scale, energy, and groove of the linen before ‘beginning.’ There are no sketches or predetermined compositions, I want to figure it out with and in front of the viewer, so that they can read how the piece was formed. When color eventually participates it begins through a hierarchy of refracted light. I grind pure pigments with safflower oil and start with a Sumi-e like wash using broad, cheap, chip-brushes that create thin but wide strokes. While this is wet, I take a rag and begin to pull the composition out by wiping and ripping away the saturation. Eventually sketching in paint with loaded brushes reiterates or shifts the piece around. Each layer is separated with a slightly thicker layer of safflower and walnut oil to refract light, a technique common with Dutch Baroque painters, such as Vermeer. The goal is that a piece can feel thin and radiant at the same time, almost as if it is glowing from within.

At the end of every interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you would love for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

The remarkable Gaby Collins-Fernandez!