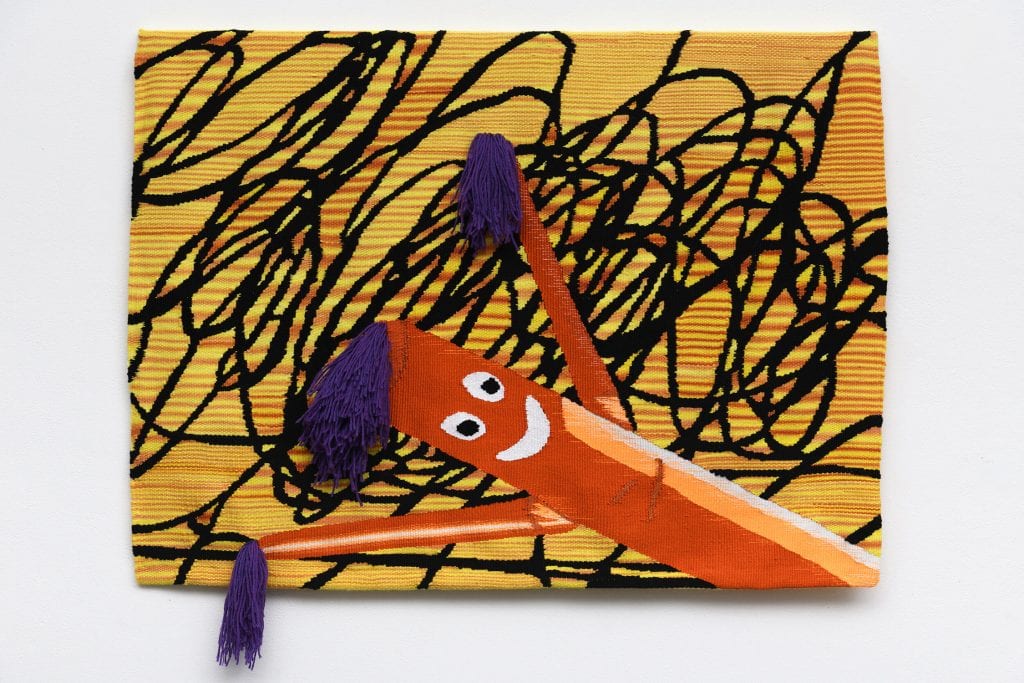

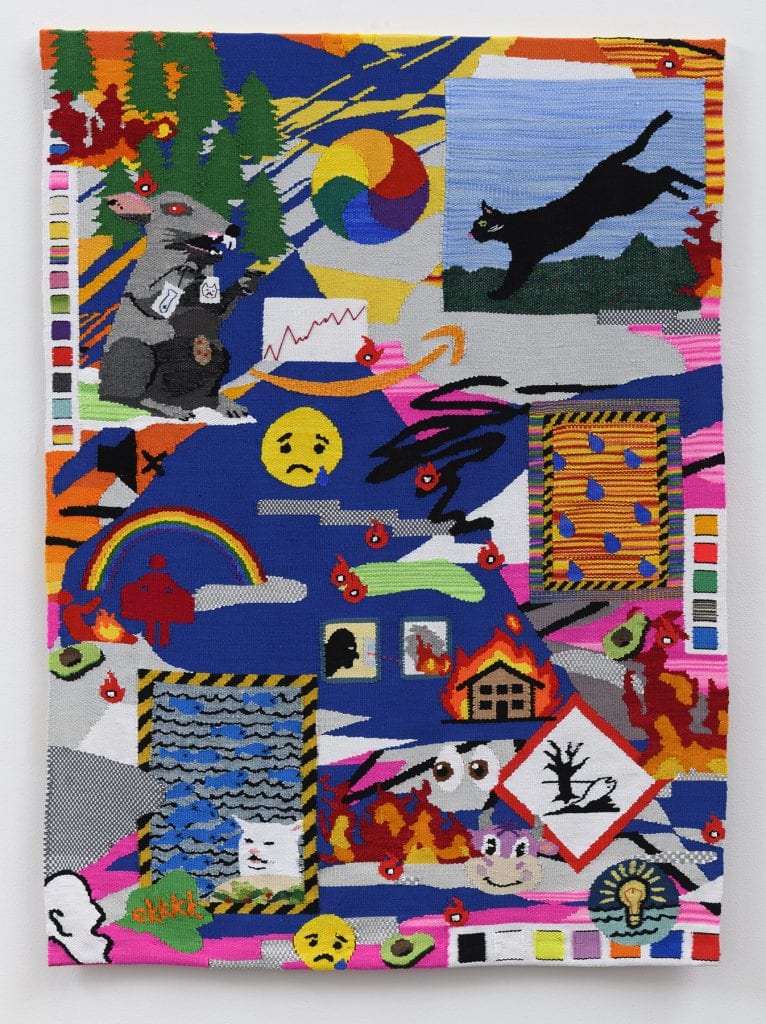

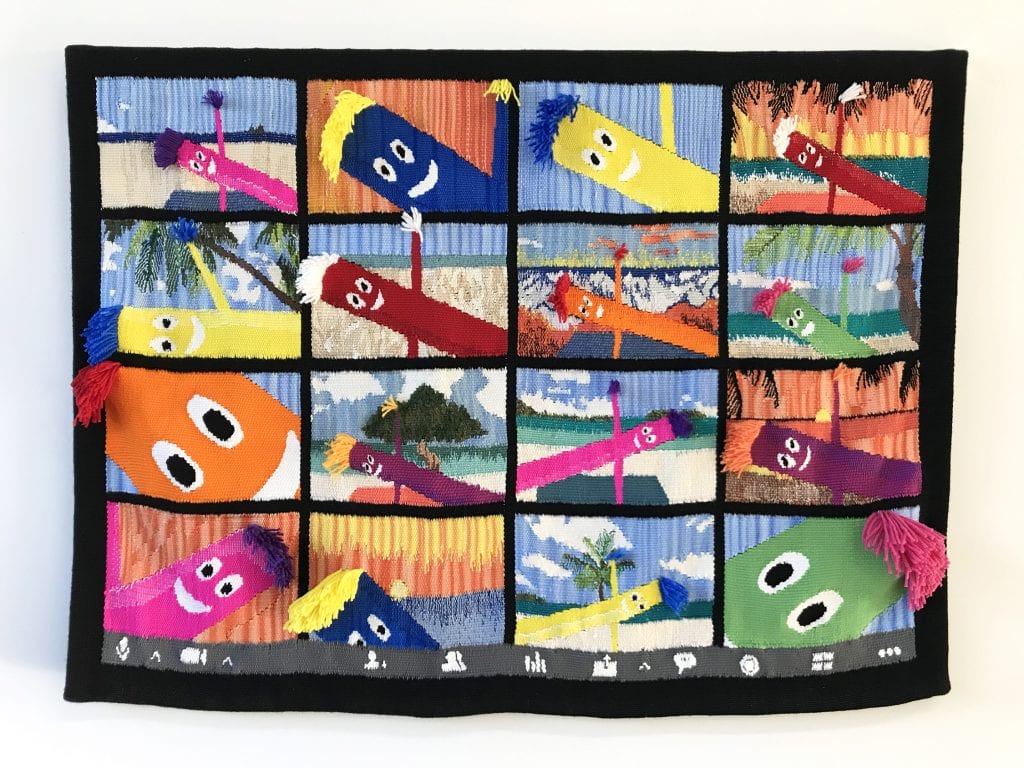

Based in LA, Kayla Mattes presents her work through the rarely-seen craft of weaving. The artist uses the meditative practice of weaving to tackle questions of memory, a life in the age of technology, and our relentless consumerist habits. Through an unmistakeable comic cynicism, Mattes’ tapestries communicate the most influential tools and symbols of today as the subject, while the intricate, historical, and politically charged medium, dialogue in each point. From Air Dancers to Cat-astrophe, to User Interface (all seen below), the body of work is truly experienced in the viewer’s mind— in seeing woven points and pixels endlessly interchanging in meaning, much like our relationship with reality and technology. Read below to learn more about the artist, her upbringing and craft.

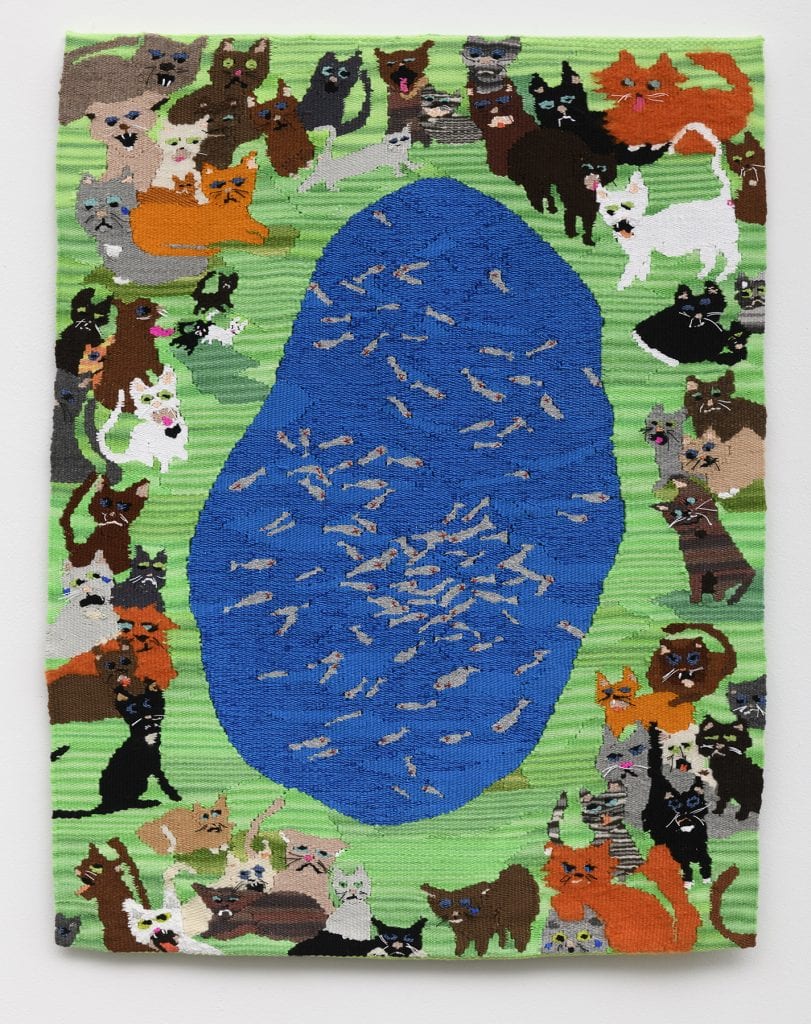

wut will they fed us when all teh fishes r gone?, 2019, Handwoven wool and cotton,46 x 35”, Courtesy of the Artist

Tell us a little bit about yourself. Where are you from and how did art first come into your life?

The idea of home is kind of amorphous for me. I was born in the desert north of LA, but my family moved all over the US frequently until we landed in Long Island, NY when I was 11. Since then I’ve kept up with a somewhat transient existence and have lived up and down the West Coast over the years, but I studied Textiles at RISD before heading out West. I’ve been in LA for about a year now and plan to stick it out.

Like most artists, I was naturally drawn to making things as a child. I think all the moving heightened my introversion, which meant spending a lot of time drawing cartoons, playing around on the 90’s-early 2000’s internet and messing around with building-oriented computer games. My grandmother in California was an art teacher and would always be making her own documentaries and books, and learning crafts like basket weaving, which she’d involve me in when I’d get to see her.

Influencers, 2020, handwoven wool, cotton, polyester, and mohair, 38.5 x 48”, Courtesy of the Artist

Has your work always taken on the same style it currently embodies?

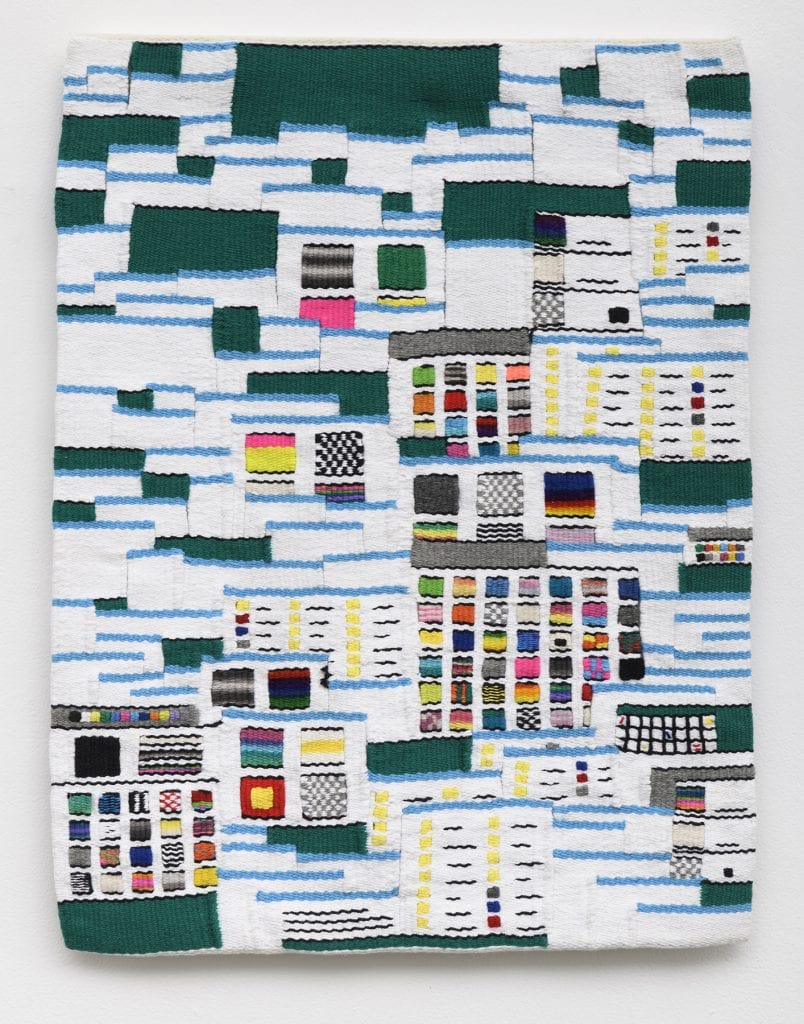

It’s shifted, but there’s a clear foundation. My earliest tapestries were abstractly looking at the format and geometries of user interfaces by breaking them down to their bare bones through the woven grid. I like the idea of translating fleeting screen-based moments into a static and tangible thing that’s structurally related to its origin. When planning the set-up of the loom, it’s like choosing your resolution. The denser the warps, the higher the resolution. It’s all a grid, and when you’re working with structure-based weaving, where weave drafts are involved, you’re using algorithms to construct the fabric. There’s a historical relationship between the two which was the guiding dialogue with my early weavings. At a certain point I felt like I couldn’t say what I wanted to say with abstraction, and my tapestry skills became stronger, so I started working in the chaotic and representational style that’s evident in my work today. The underlying reference to the structural relationship between weaving and computing still exists in the work, but now I’m building pictorial narratives steeped in humor and societal reflection, specifically in regards to the cultural milieu of our screen-based world.

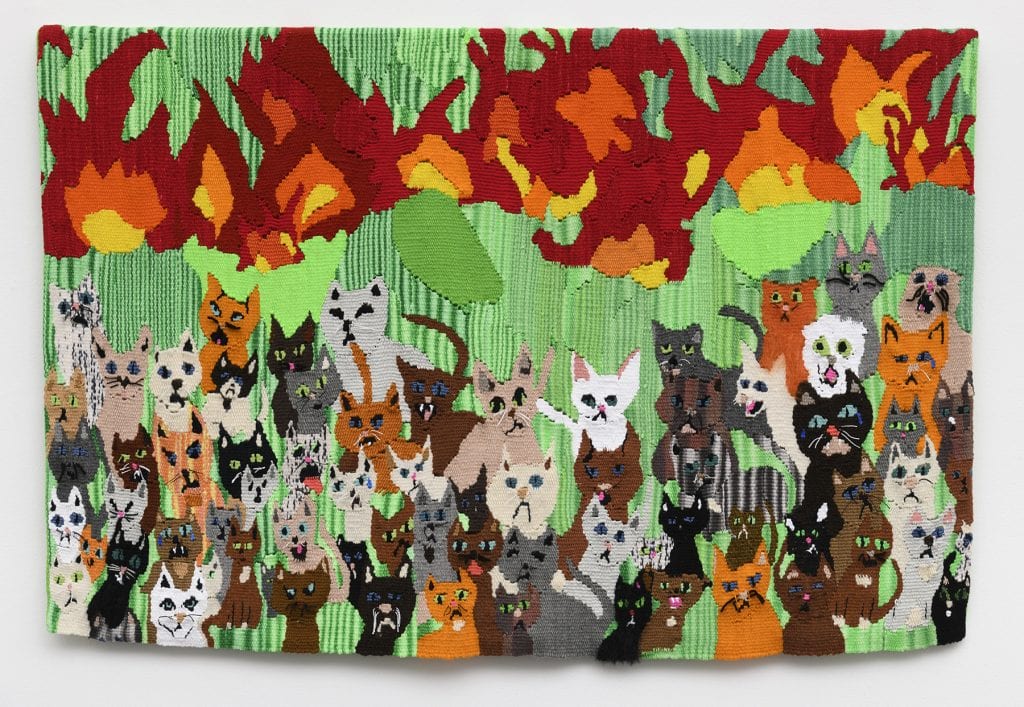

Teh climbin spotz haf burned, 2019, Handwoven wool and cotton, 34.5 x 53”, Courtesy of the Artist

What is your process like? How do you begin a work?

My pieces start with drawings and photoshop collages. With a projector I transcribe the final collage to scale on paper to make my tapestry cartoon which gets attached behind the warps, and acts as a guide that I work from while weaving. I also dye a lot of the yarn, so before I start each piece I plan out any new colors I need to make. The distorted gradient areas in my tapestries are the product of an intentional dye strategy to mimic pixelation and distortion when the yarns are woven. From there the process of tapestry weaving involves working upwards and piecing together forms across the surface of the warps. It’s kind of like drawing on the loom. I’m working with the simplest of weave structures, plain weave, to build up the landscape of imagery in the pieces. The whole process has a planned structure to it, but there’s also fluidity in how I can choose to work with material to create shading, articulate forms, and texture.

3.5 hours of internetting, 2015, Handwoven cotton and wool, 30 x 22 in, Courtesy of the Artist

From where do you draw inspiration?

Things like social media, current events, signage, memes, advertisements, digital interfaces, animals, plants, and typography. I think that my location also organically influences the work. The Zoom pieces are filled with Los Angeles emblems– palm trees, gas stations, and influencer culture. My previous series about climate grief, as seen through the lens of cats, was made after several years of living adjacent to wildfires.

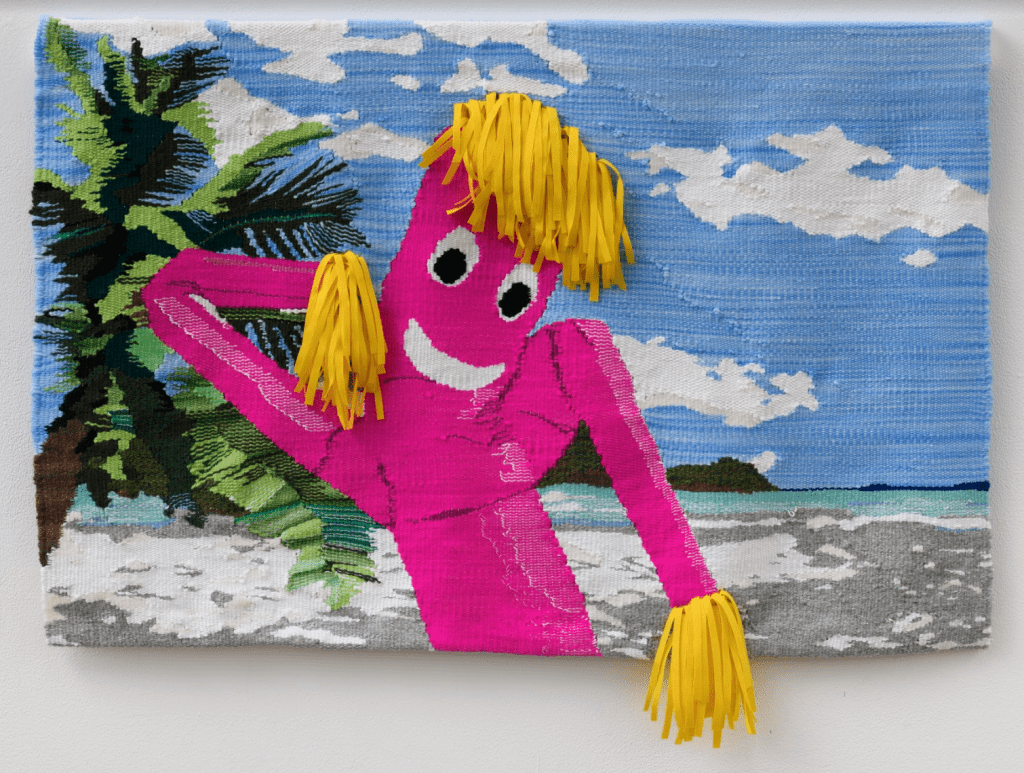

Zoom Background, 2020, Handwoven wool, cotton, and canvas, 24 x 36.5”, Courtesy of the Artist

Walk us through a day in the studio.

It depends on where I’m at with a piece. I only work on one weaving at a time. If I’m in planning mode I spend my days drawing and photoshopping, mixed with some visual research and writing and walking and likely procrastinating. When I’m weaving, it’s nonstop days of working on the loom, while listening to music, podcasts and thinking about ideas for new work. My studio is in the Flower District of downtown Los Angeles which is adjacent to the Fashion District and many other commercially distinct city blocks. Every day I take a break from weaving and go on a walk, often photographing fabrics, city signage, plants, and oddities of the city that I pass along the way.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯, 2020, Handwoven wool, cotton and polypropylene, 30.5 x 42”, Courtesy of the Artist

Can you tell us about your relationship with weaving?

I started weaving about twelve years ago in the Textiles department at RISD, where I learned how to work on floor looms and program jacquard. I picked up tapestry weaving on my own several years out of school. I was drawn to the graphic capabilities of the process. It took me some time to put together how working in this craft medium as an artist holds so much power and will always play a part in how the work is perceived and what it means. The binary ideologies of art vs. craft, how that relates to gender, the labor and time aspect of the process, and tapestry weaving’s political, technological and narrative history are all things I think about as a weaver.

Premonitions of Smudge Lord, 2019, Handwoven cotton, wool, and acrylic, 60 x 43”, Courtesy of the Artist

Have you seen any changes or shifts in your work due to the worldwide shutdown?

I’m interested in the narrative history of tapestry weaving and its ability to act as a material archive of our times. I riff off that tradition in my work, as a way to explore ideas related to our relationship with digital culture, socio-political issues and how the entanglement of these things makes us feel. Humor also plays a big part in the work, similar to the way memes operate. Since the ideas in my work are interrelated with the current moment, the pandemic has naturally come into play with the tapestries that I’ve been making throughout 2020.

With my new Zoom series I’ve been using those inflatable dancing tubes from gas stations and car dealerships as a placeholder for humans. In varying densities of the Zoom grid, they vacantly smile with their bodies contorting in and out of the frame, in front of backgrounds that may or not be real. They are

trying to stay positive, but their emptiness and neuroticism lingers. So the series is reflecting on us, and how we’re socially operating within this sudden shift in day-to-day norms. The tube people are also so erratically humorous in their movements and disposition, but we never get to see them in a frozen state. This made me think about Eadweard Muybridge’s motion studies, and how embedding them within the Zoom grid would result in a similar study of movement.

Untitled_paint, 2015, Handwoven cotton and wool, 30 x 22 in, Courtesy of the Artist

Does your work reference any Art Historical movements?

Well I guess I just referenced Muybridge, but I think my work is more driven by the everyday. I’m sure there’s some subconscious influences. Roger Brown and Hannah Ryggen are two artists whose work I’m always thinking about.

What’s next for you?

There is still so much to explore with my Zoom series. I just finished a new one inspired by the gas station dance party that I encountered in my neighborhood on the day that Trump went down, but there’s many other ideas on the queue.

Zoom Yoga, 2020, Handwoven wool, cotton, polyester, and mohair, 34.5 x 46.5”, Courtesy of the Artist

At the end of each interview we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love and would like us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

My studiomate Corey Pemberton!