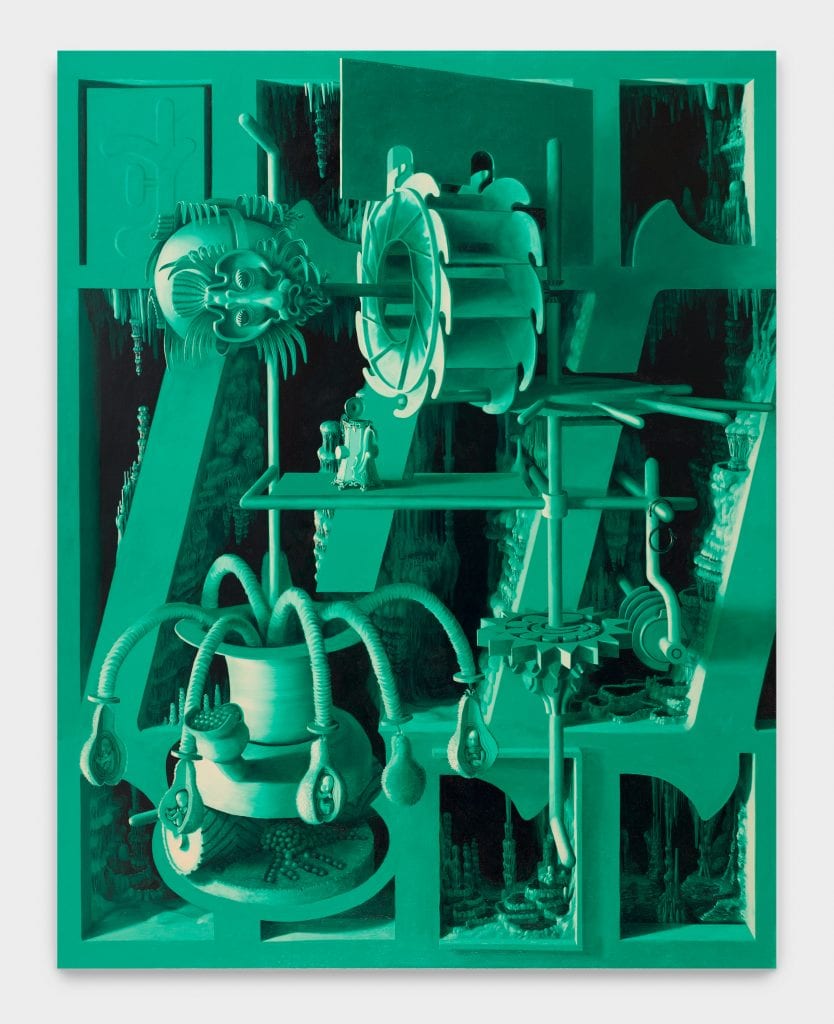

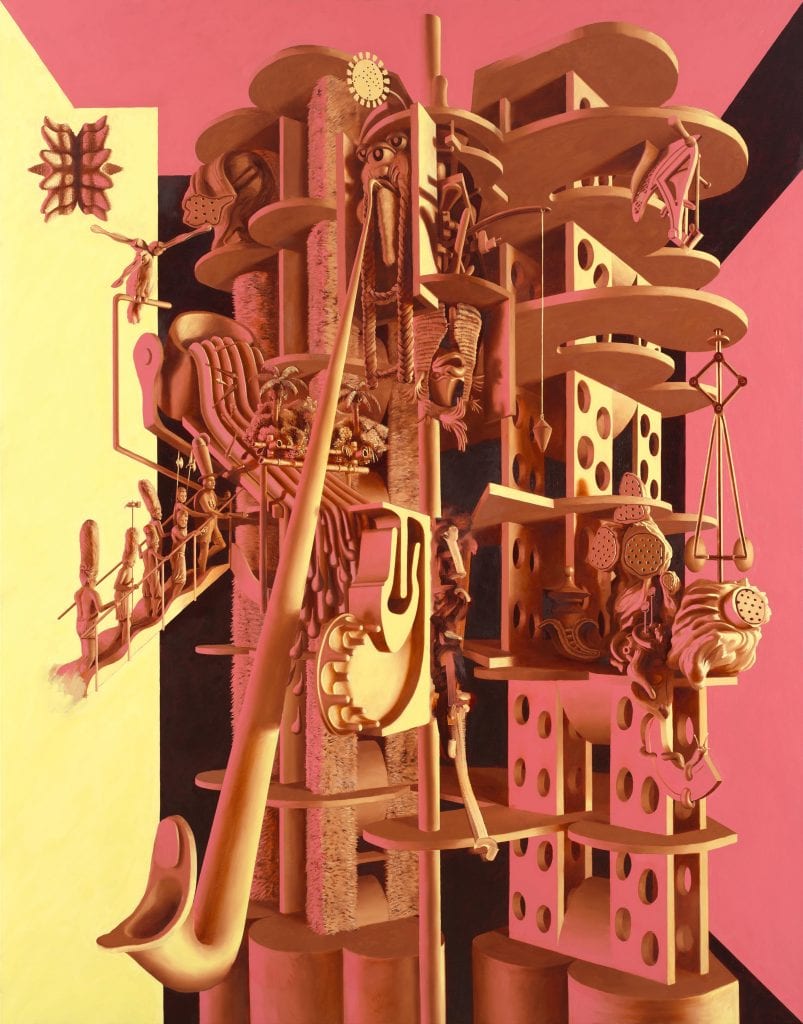

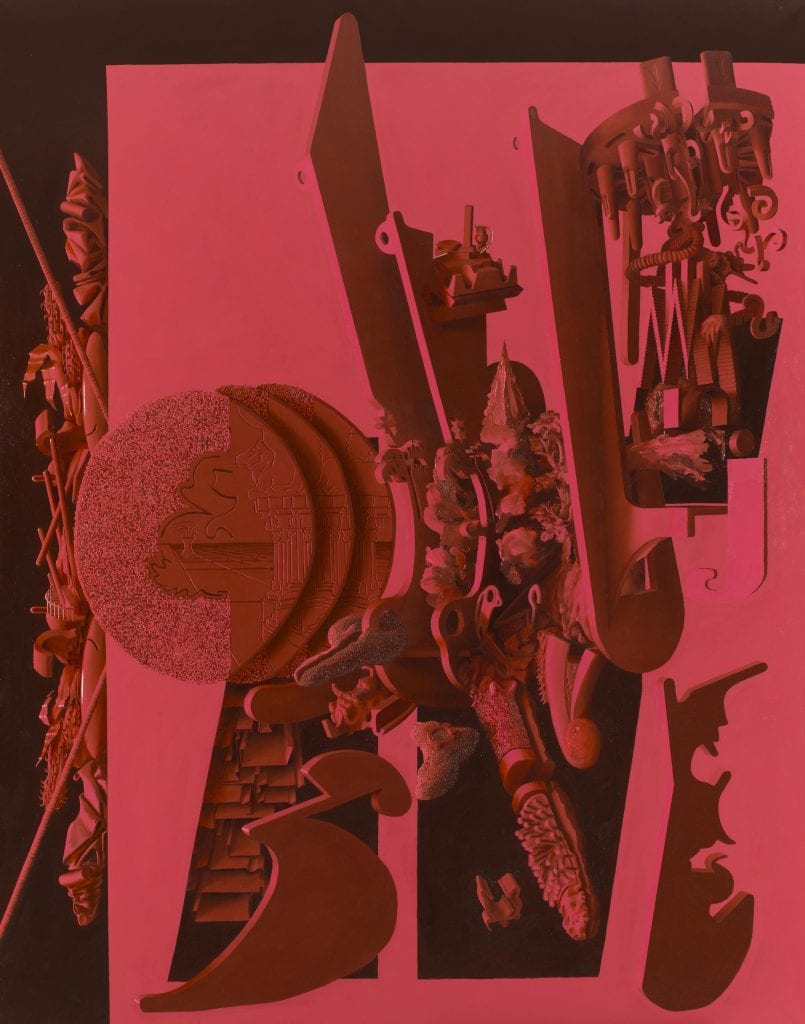

Through the cogs and mechanisms of the intricately detailed compositions of his paintings, Tom Waring calls upon to the viewer a fascinating mèlange of Old Master painting techniques and contemporary imagination. The artist works strictly through oil paint and explores the human capacity to interpret depth through two contrasting colours. In his practice, the artist uses his stocked toolkit of art historical knowledge to bring to life his gargantuan creations. The level of detail in each composition makes the viewer wonder whether they’ve spent enough time to drink all the information in. Read below to learn more about the artist, his background and his unique style.

Eezlebulb Pip, 2019. Oil on linen, 63 × 55 in., Courtesy of the Artist and Downs Ross, NY

Tell us a little bit about yourself. Where are you from, and how did art first come into your life?

I was born in Reading, which is slightly West of London. I’m not somebody who has a fateful story of when I started to draw or paint, it wasn’t really like that. My first encounter was when I was about 16, and I was looking at it, rather than making it. I started making art when I was 18— about the month before I decided to go to art school.

Has your work always taken on the same style it currently embodies?

In uni I went through a few phases. I started looking at the Old Masters, early 20th c. painting, and it kind of progressed through the ages chronologically as I advanced in my studies. I did my undergrad at a university in west coast Wales called Aberystwyth, where the geography is very peripheral and the ethos there is attendly outlying relative to London, which allowed me to dive into the world of classics. When I came to London, I had to catch up in all the new and contemporary work that was being made. The work I make now, is the product of that toolset of old knowledge, and how to make something singular with it.

Grotl, 2020, Oil on linen, 180 x 140cm., Courtesy of the artist and Downs Ross, NY

What’s your process like? How do you begin a work?

In my head, I always approach painting from the premise that the paint wants to point away from itself, and it wants to signify something. It;s almost an animist assessment. I’m always looking for paint to be a sign post to something, and that became an overarching theme in my work. I tube my own paints to get the right tones and viscosity, and stretch my own canvasses and mix my own mediums. The colours become almost the moment of conception for each painting, as each palette has its own unique character which provides connotations that then bleed into the work. Most of the time I begin with very rough marks on canvas, to get an idea of where I’m heading, rather than hashing out sketches. From there, I work out the details of what I’m going to do next. So, after the first marks, figuratively speaking, I would say the painting sort of makes itself from that point. Afterwards, throughout the process, I do orientate myself with manual and digital sketches, but they’re cues for the self-generation of the overall composition.

Installation view, Consistent Estimator, 2020, Courtesy of the artist and Downs and Ross, NY

Walk us through a day in the studio.

My studio isn’t very close to where I live. I get here at about midday, and work until around 2 or 3 in the morning. I can sleep in a place that’s near my studio, where I can come back in the morning and finish what I’m working on. I’ll leave at around five and then head home. I’m an owl when it comes to sleep, and I’ve always found it very useful to hide away for long periods of time, which I’ve felt is beneficial for the work and the paintings themselves. It takes an hour just to mix my palette with all the right mediums etc, as I;m very methodical when I set myself up, and that will last me for maybe 2-3 days. I work like this in waves, and then whenever I have a series of canvases to stretch, something to build in my studio, or something to write I fall back on a more human life.

From where do you draw inspiration?

I start with rough, very basic marks. These ideas normally come to me whilst working on a previous painting. So one painting can form the next. I made one painting I made when I was studying in my postgrad at Wimbledon, that I feel was a seachange painting for me, and I’m always aiming to ensure all the other paintings advance beyond that point. (Hurenbaal, 2017) In a sense, I’m in a years-long dialogue that connects contiguously work by work.

Hurnebaal, 2017, Oil on linen, 139 x 169cm., Courtesy of the Artist and Downs Ross, NY

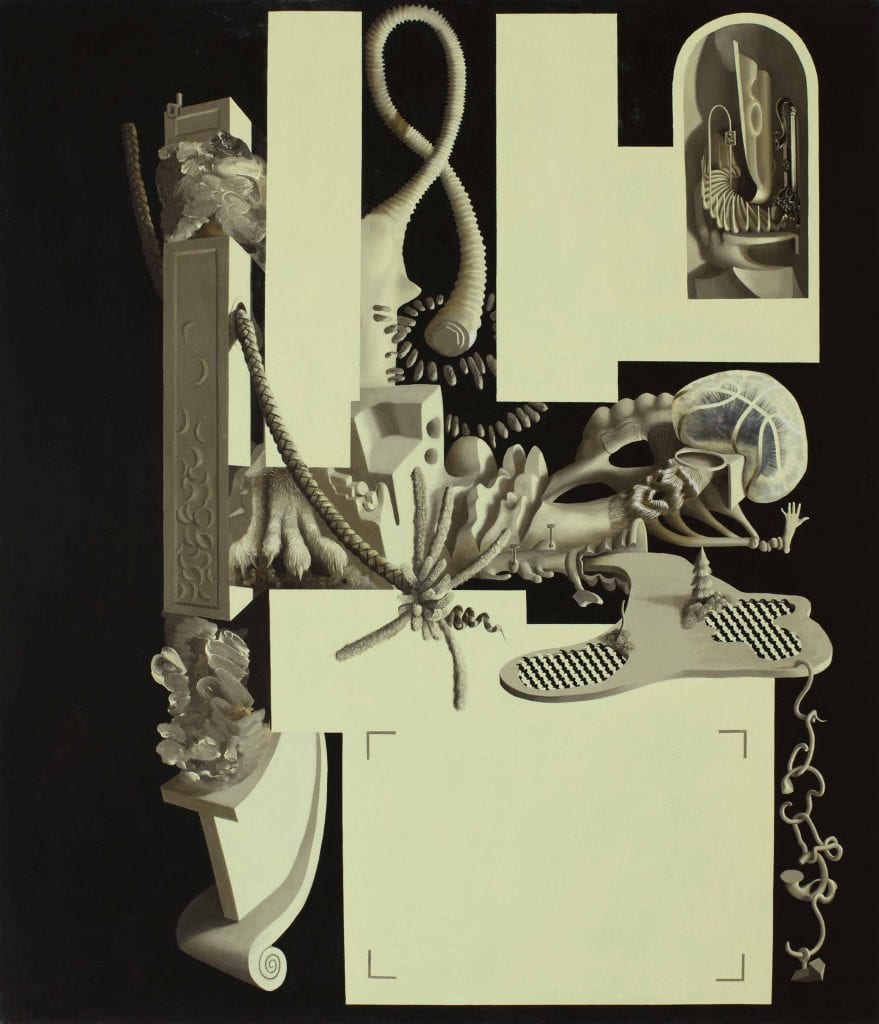

Tell us about the bi-tonal approach to your paintings.

My route into painting began in a very historically-enhanced environment. There, I learned about how people created paintings in the past. You get to delve into all the pigments, varnishes, resins etc. that came about in the past. One of the principal ways in which Old Masters from multiple time periods made their paintings was through the Grisaille approach, which just means gray layer, and was an analysis of what is going to be light or dark within the composition. If in a painting you worked out what was light and dark, the 3D-ness is there without the need for color. When I came to London, I started making paintings using this grisaille stage; and, I liked that indexically so that’s where I left it. So from there, the bitonal color palette coordinates from what I was doing in Aberystwyth, and I started playing with the idea of two different light sources and seeing what came out of that, which further complicated the composition. Leaving the painting in the grisaille layer reveals more a process of me tapping into this fiction of what one makes with representational paintings and how classicism inherently contained the means to turn them inside out. For representing representation itself. Grisaille remains a great conduit.

Hutch Skutch Skoa, 2020, Oil on linen, 180 x 140cm., Courtesy of the Artist and Downs Ross, NY

How do you come up with the titles of your works?

That form when I was studying people’s reactions to my work. Because in my paintings there is no identifiable context, people would refer to my paintings through their colours. And as an effect, people were using syllables that sort of came from their perception of the paintings. This brought me to think about the Bouba /Kiki effect. It’s the test where you have a rounded and a spiked shape, and ask which of them is Bouba and which is Kiki, cross culturally, everyone could tell you the same answer no matter their language or culture. I was thinking how I could make titles echo the appearance of my paintings. Take for instance (Grotl, 2020, Oil on linen, 180 x 140cm). This work has alcoves seemingly set into the surface of the canvas, that later were manifested as literal caves. In English, the word for a smaller self-contained cave is grotto, similar in other languages too, so the “gro” in Grotl came from that initial syllable. And, somehow I won’t reveal, I came out with the L at the end.

Installation view, Consistent Estimator, 2020, Courtesy of the artist and Downs and Ross, NY

What larger questions do you think your work asks?

I believe it’s about how malleable meaning is when it comes down to visual information. We are very habitual when it comes to interpreting visual information outside of art. I’d go as far to say that we are all experts at things like synecdoche, metonymy and skeuomorphism, even though we were never specifically taught it, and are rarely aware when we use it. Behind the fluency with which we digest images there is a well of linguistic complexity that can delve into how meaning is constructed, how communication dually comes derives from and drives media— be it speech, visual, or material. When I was studying, I was constantly looking for a reason to paint, and I found one in the unruly nature of the creative process. Eventually there has to be a laugh in the face of adversity when it comes to making my type of work. Not only in a practical

sense because of their size and intricacy, but also with regards to my intent, laughing towards the kind of cynicism that I think builds around a process that can be so disobedient and disorderly. There is a sense of sincerity in painting that I’m trying to nurture in my work, a sincerity that I think has stayed with me from my time in Aberystwyth. I see the cynicism as a kind of end game scenario despite it being an endearing and characteristic part of today. Laughing in the face of this cynicism is where my work lives

Pimsupun, 2019, Oil on linen, Courtesy of the Artist and Downs Ross, NY

What’s next for you?

My solo, “Consistent Estimator”, opened at Downs Ross, in New York, right before the Covid lockdowns and it still feels extraordinary it managed to get the attention it did. In the immediate future we have FIAC Paris, that launched March 3rd. I can’t yet announce anything after that, but there are exciting things in the works.

At the end of each interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love and would like for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

I studied with Frederic Anderson, and trust his opinion a lot.