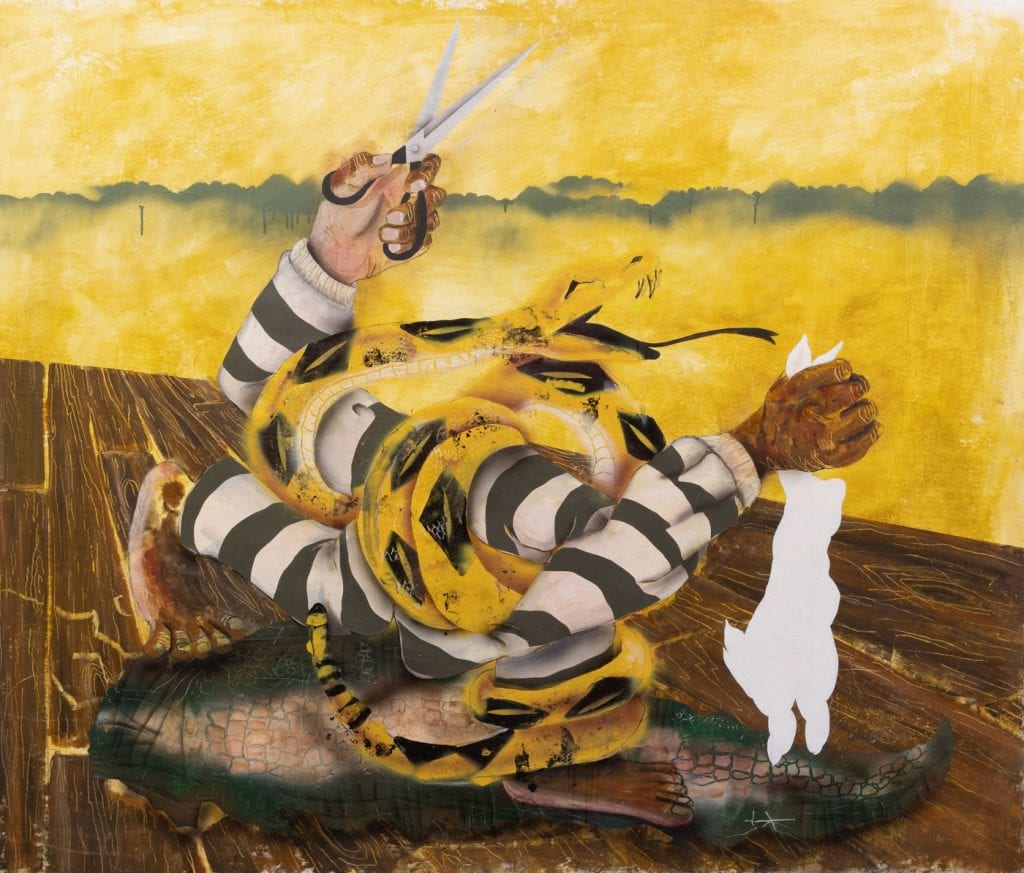

Pat Phillips’ work is full of multifaceted elements, both in styling and meaning. Phillips, who grew up primarily in a small town in Louisiana, found his way to art through general cultural references. He embraces this entry point, creating paintings that discuss the Americana subculture, as well as the current social and political threads running through American culture. Phillips had a stand-out work at this year’s Whitney Biennial, a large scale mural symbolizing incarceration, the insulation of suburbia, and the U.S.–Mexico border.

When did art first enter into your life? When did it become something that you decided to pursue seriously?

I’ve always been into drawing. I guess my earliest memory, is my dad would draw cartoon characters for me and my brother. We’d bring him one of our Ninja Turtles and he’d crank out a drawing on a poster-board for us. From there, I started making my own comic books with friends, then started writing graffiti around 13.

I’d like to say 19-20, when I started college, but honestly, I spent most of that time l painting graffiti. Probably when I dropped out of school a few years later was when I really started taking painting “seriously”.

How does your upbringing play a role in your work?

Being from a working middle class black family, art wasn’t really a thing outside of comic books, cartoons, and clothing graphics. My mom was a huge Thomas Kinkade and Norman Rockwell fan…so we had a few generic prints and collector plates, along with random prints of floral paintings and black baby angels in the bathroom. I remember watching QVC with her once and she asked me why I couldn’t just paint things like Kinkade haha.

While we lived in England, she amassed a collection Lladro’ figurines and was always collecting stuff. Obviously, none of this would be considered “high art”, but this is what you see in middle American households. I think at an early age, it taught me to appreciate the sentimental value of objects and looking at pictures.

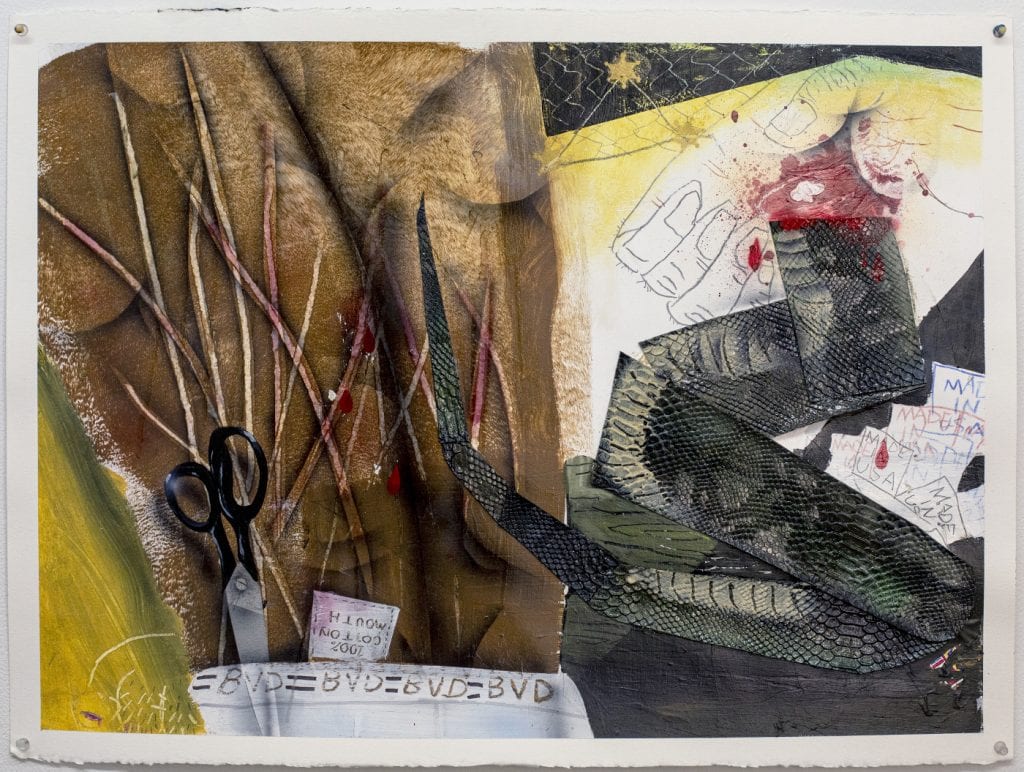

In the paintings, my interest in cultural and subcultural Americana, is not only a way to have more inclusive conversations through recognizable imagery, but a way to address our own ignorance.

Truth is, I grew up in the deep south in the 90s, so I find myself looking back and processing a lot of things that at the time, seemed pretty normal.

Are aspects of your work autobiographical?

Of course, even though the work is typically addressing a larger idea, at its core, there is usually a personal narrative being told in some capacity.

What is a typical day like in your studio?

I work on multiple things at a time. I usually have a few paintings going, while having paper spread out amongst the floor. I have a real issue with waste. So generally, my sketches and works on paper are comprised of over mixed paints from my larger works. This actually helps free up my process, as I like to let the majority of my paintings build up organically. This usually means no preliminary sketches. This guttural approach of mark making and pushing paint around keeps the work from becoming formulaic. I credit a lot of this to graffiti and drawing constantly in black-books. It really feels like I’m learning how to paint all over again sometimes, which can be frustrating, but is exciting.

I actually spend a lot of time outside of my studio doing other things. To be honest, what happens outside my studio is probably the most important. I associate with a lot of people who don’t make art or have very little interest in it. So this is very helpful to my studio practice…both mentally and aesthetically.

What other artists working today most inspire you?

Trenton Doyle Hancock, Jonathan Lyndon Chase and Tschabalala Self are all amazing. The homies who I grew up painting trains with. Some of those guys are crusty…some of them are 40 hour a week got 2 kids and family type people, but nevertheless have been getting it in for 20 years.

Is there a certain emotion you want a viewer of your work to walk away feeling?

I want my viewer to be open to conversation. To be able to laugh sometimes, but also be able to look at their position within the painting. There is a level of nuance within the work that will allow the viewer to immediately see what they want, while forcing them to walk away with something that might not be as easy to digest. They will either see themselves within the faceless limbs or as the voyeuristic outsider.

The emotional prescription is unique to each individual.

I look at some of my own pieces and feel empowerment, while I’m sure others might sense fear or aggression.

It’s complicated…like the OJ verdict.

You’ve had some landmark moments this year, from painting a mural in The Whitney Biennial, your first solo exhibition in New York, and being included in Punch, the standout group show at Jeffrey Deitch LA which fellow artist Nina Chanel Abney curated. What have these experiences been like?

I remember sending Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta my mock up sketch, which consisted of some foam-core and essentially a napkin sketch of the mural image and thinking to myself, “These people are going to freak out when they see this crap!” I’ve been making work for nearly 10 years now, but it was definitely the first time that I was thinking, “What did I get myself into.”

Despite working from my small town in Louisiana (I moved last year), it’s been good. Coming from a graffiti background and then being asked to create a site specific piece for the Whitney, you definitely create this idea in your head as to how things have to go. Sure, there’s a level of bureaucracy that can be annoying, but seeing their sense of trust in my process and work was dope.

As I mentioned earlier, I feel like I’m still learning and figuring out my own work everyday, so it’s just been exciting to be apart of the conversation.

What’s next for you?

Going to be hiding out at the Fine Arts Work Center in Massachusetts for the next 7 months.

I have a show at M+B gallery in February.