Tariku Shiferaw is a mixed-media artist looking to rewrite the history of Abstract art. Frustrated that all of his glorified predecessors were overwhelmingly white male, Shiferaw discovered how to create his own distinct marks, full of clever references to his culture and its place in the world. Shiferaw’s work weaves together different historical narratives of Black culture to create deeply meaningful, powerful pieces. Shiferaw is based in the Bronx, NY.

Tell us about yourself. Where did you grow up and when did art become a part of your life?

For the most part, I grew up in Los Angeles, California and moved to New York over five years ago. Art became a part of my life when I was a kid. I really didn’t know it at the time, but seeing my older brother draw cartoon characters so precisely and playfully with a regular pen became my introduction to art. I found a desire to simply draw things. Later, I pursued it more seriously.

How did you arrive at your latest series of works?

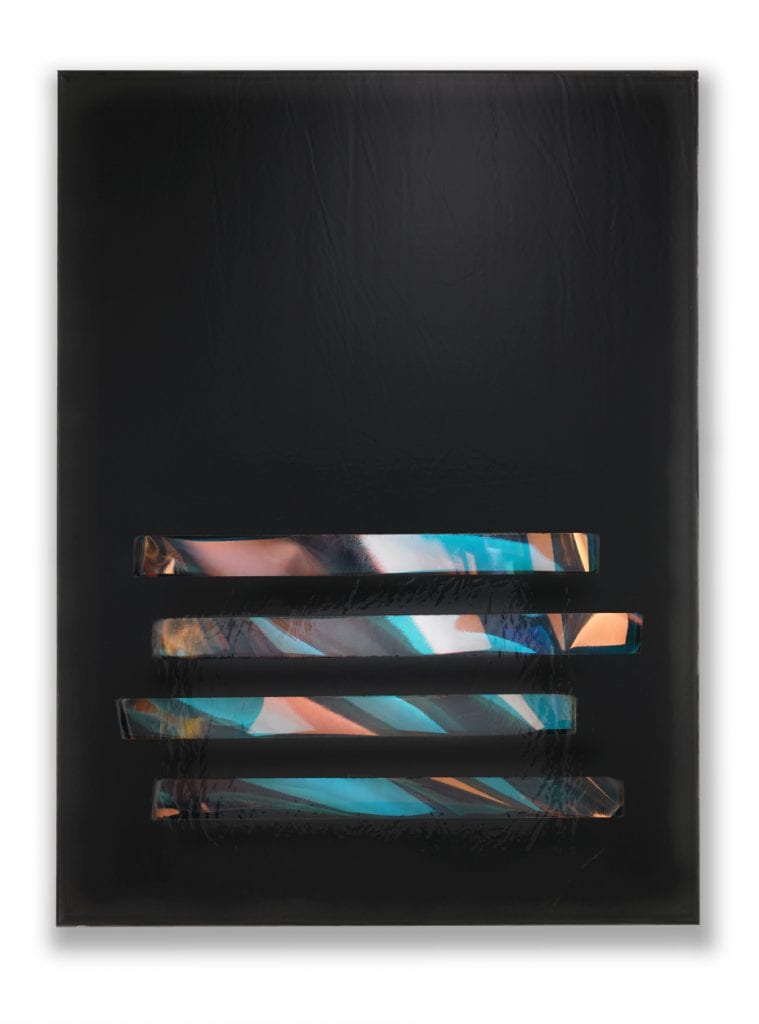

My latest body of work is titled One of These Black Boys consists of paintings, sculptural objects, and installation. Through this series I explore the idea of mark-making in order to address the physical and metaphysical spaces of painting and societal structures. In the discourse of painting, the term ‘mark-making’ is a word used to describe painterly gestures that mark the painting surface. This term is especially prevalent within the conversation of abstract paintings. With this in mind, I began to think about the role of the mark-maker and how I fit in the picture. For so long, Western Art history had credited the white-male artist as the sole contributor to the movement of abstract art, while ‘othering’ everyone else. Even when occasionally recognizing white female or Black artists as contributors, the interest remained mainly on the white-male as the mark-maker and producer of culture through art. This led me to re-appropriate the term ‘mark-making’ so that it functioned outside of the discourse of painting. I began to physically place a band of stripes over painterly gestures. In a way, this allowed me to place my own mark over well-recognized atavistic gestures. Secondly, I began to title each work based on Hip-Hop, R&B, Blues, Jazz, and Reggae song titles. This method of titling proved to introduce another layer of marking, which referenced something outside of painting and visual art.

What artists, both living and dead, most influenced your practice?

I’ve looked at so many artists throughout my career, and many have impacted me for various reasons. Here are some that come to mind: Jack Whitten, Ad Reinhardt, David Hammons, Julie Mehretu. Chris Ofili, Wangechi Mutu, Mark Bradford, among many others.

You are interested in examining symbols – their histories and their different meanings – what are some symbols that you have entered into your art and why are you interested in them specifically?

I’m interested in geometric shapes, which carry numerous meanings do to their history of having existed amidst a variety of groups of people and their cultures. As a result, geometric shapes do not mean anything unless they’re placed within context. I use rectangular shaped horizontal stripes in my work. I’ve always treated these forms as a deconstructed version of “x,” where they function similarly as “x” does in society – this is to say, with multiple possibilities of meaning. I’m interested in the in-between places of meaning, where there’s no true resting place for the form or a singular meaning it’s tied to. The non-referential quality of geometric forms allows for possibilities that well-defined symbols couldn’t perform. I’m also interested in the ambiguity these forms ignite within the work.

How did you arrive at the black and blue color palette that appears in many of your work?

I’ve always liked blue; it’s my favorite color. However, I’ve never noticed a juxtaposition of black and blue until I accidentally dropped some black paint onto my blues. As I began to investigate my deep fascination for placing these two colors together, I came across many things that mimicked and paralleled the relationship between the two. It’s often a conceptual or metaphorical correlation. For instance, the night sky against the day sky, the music genre (the Blues), and the bruising of the black skin. The dichotomy presented in the relationship between the two colors became very loud. The color black is often tabooed in society, while blue is revered as the symbol of the heavens above. However, in the Blues, the blue represents a type of melancholy, it describes the hardship of life caused as a result of having Black skin. Songs in this genre describe the bruising of the skin into black and blue, while simultaneously placing hope in the liberation of the soul. These colors are super abstracted and can weave in and out of a number of topics.

Tell us about your process. How do you approach beginning a work and how does it progress once started?

I usually work with an idea. If I were painting, I’d start with a group of paintings. Often times most get messed up during the experimental stage, but one or two do come out successfully. If I’m working on a sculptural piece, it’s usually just one at a time. Experimenting with form is very important to me, so I always leave room for that. Often, no one will see my experimental works for a year or two until I’m ready to talk about the piece or idea. I always begin working with an idea and develop it both conceptually and materially. I expand on these ideas within a series I’m thinking about.

What’s next for you? What has you excited right now?

I’ll be participating in Volta New York 2019 on March 6th – 10th. Honored to have Addis Fine Art represent me in a solo booth.

At the end of every interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

Alteronce Gumby and Marvin Touré. They’re both great New York based artists whom I look forward to collaborating with in the future.