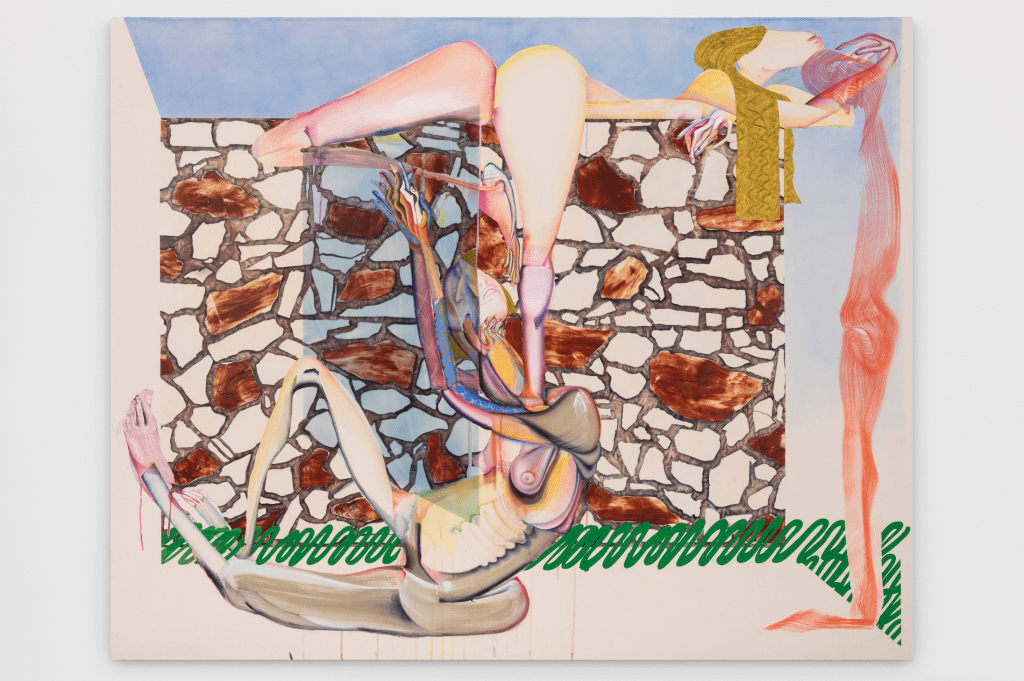

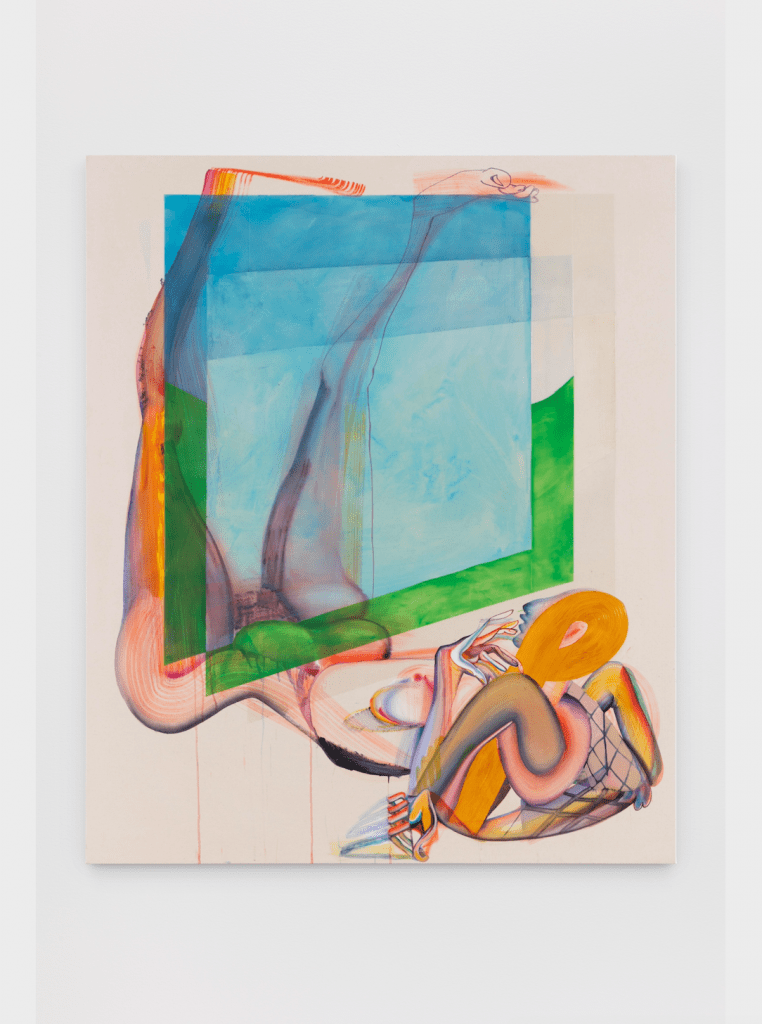

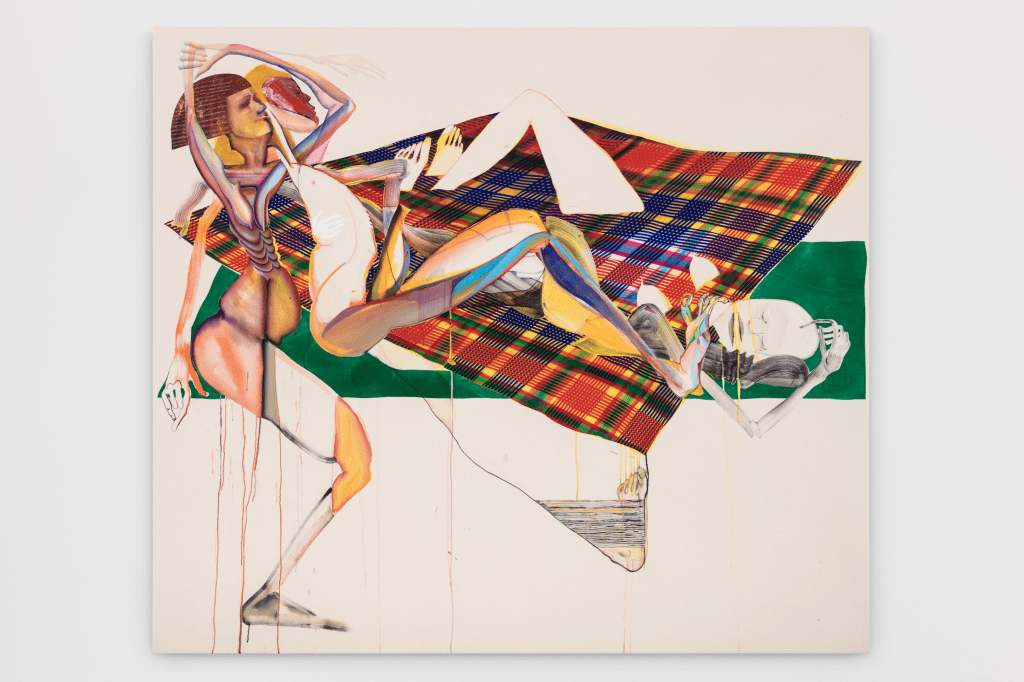

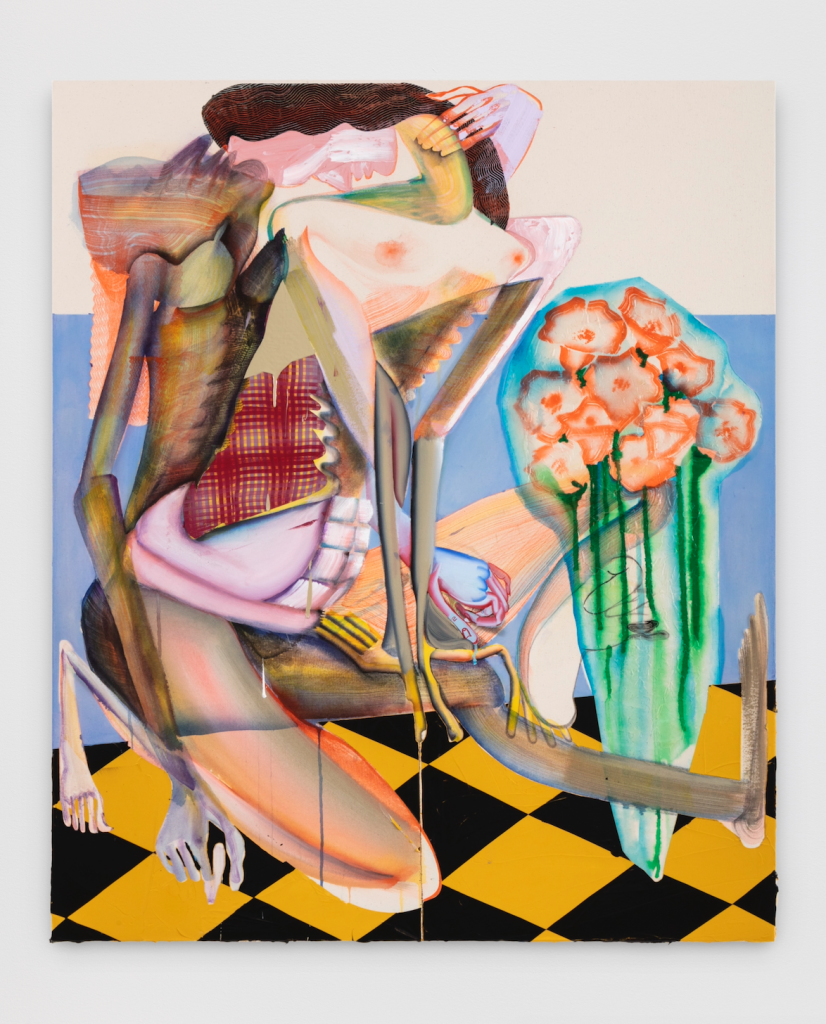

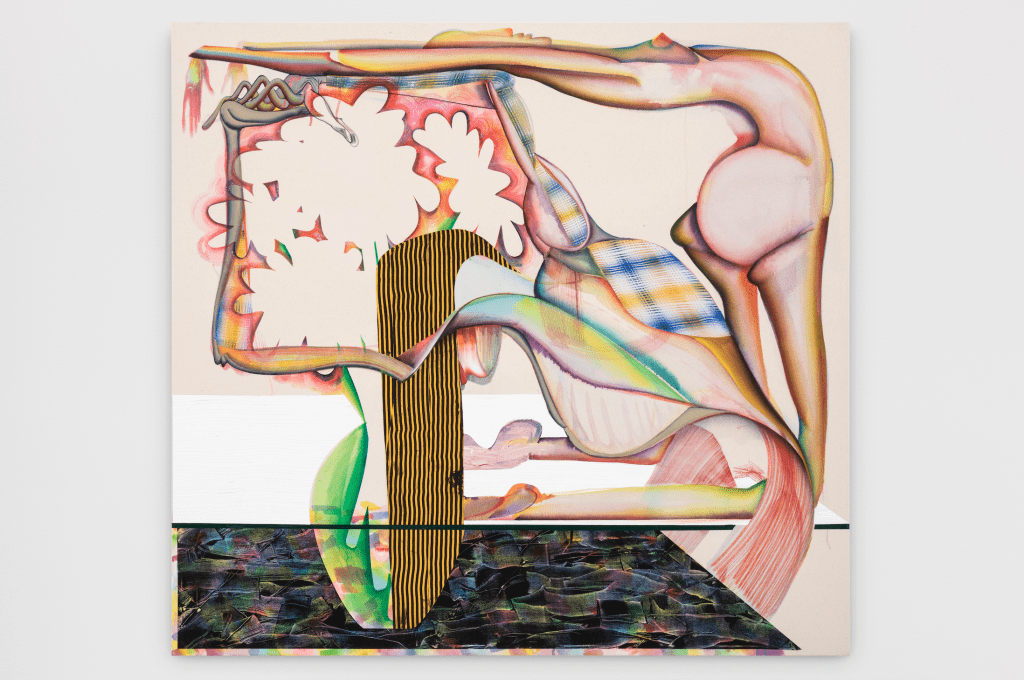

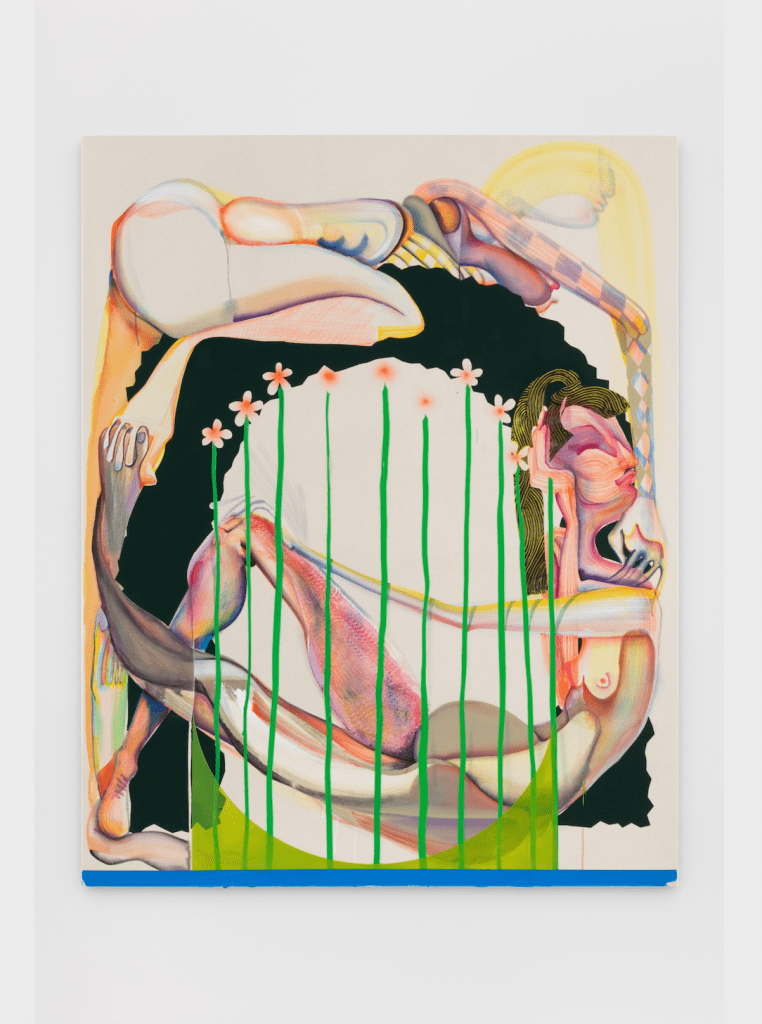

To view Christina Quarles’ work is to experience a certain kind of freedom that can’t be explained in words. Quarles’ work possesses a painterly language so unique and unlike anything else in our current environment. Grounded in certain traditions of figuration and pattern-making, Quarles transcends all categories; Her works are seemingly untethered to any Earth-bound elements. Coming off of a stand-out solo exhibition at Regen Projects in LA this past spring, Quarles’ impact is just starting to be felt. Quarles is based in Los Angeles, CA.

What themes does your work engage?

As a Queer, cis-woman who is Black but is often mistaken as white, I engage with the world from a position that is multiply situated. My project is informed by my daily experience with ambiguity, which I understand to be a point of illegibility resulting from an overabundance of information as opposed to the vague which is illegible dues to a lack of information. I seek to dismantle assumptions of our fixed subjectivity through images that challenge the viewer to contend with the disorganized body grappling with this ambiguous state of excess.

Your work often contains human anatomy. Has this always been an interest of yours? What do these elements mean to you?

I took my first figure drawing class when I was 12—it was actually kind of by mistake that I was placed in an adult nude figure drawing class as a kid, but I was really excited to learn to draw the body from a live model. What I’ve always loved about drawing the figure is that it is such a reflective process. I can relate to the weight and strain and bends and curves of the bodies I paint because I am in my own body when I paint them.

Your paintings have a lot of different layered elements to them – almost in a collage like fashion. How do you build up your work?

I never start with a sketch, though I do continue to take figure drawing classes to practice my muscle memory of the figure. When I start a piece, I begin with abstract gestural brushwork. Just like making images from clouds in the sky, I will continually step back and observe my work at this early stage and begin to pull out the figures. Once I start to have the figures come forward I will photograph my work and bring it into Adobe Illustrator and play around with different patterned planes and still life elements that can interact with the figures. The paintings are made entirely of paint, but because I mask off certain areas and use a variety of techniques and textures that draw on a range of visual referents, there is certainly a collaged sensibility to the final works. I was greatly influenced by a lecture given by Jack Whitten to think beyond the conventional expectations of both paint and collage.

Which art historical movements inspire your work?

I am influenced by many art historical movements, but I am especially drawn to the way art historical influences are disseminated across popular culture, media, and advertising. I love the way art history is quoted and misquoted in mainstream visual culture and I am just as inspired by a trip to the 99 cents store as I am to a museum.

Bodies are often seen lying on one another in your work. What does this visual presentation symbolize?

I am interested in boundary and in edge, in the parameters that define a thing, an idea, a self. Often the boundary is only made clear when contextualized in relation to other boundaries. We know ourselves in relation to others, in our similarities and differences to others. I present moments of touch to reiterate this edge of the self and how it is constantly being formed, dismantled, and reformed by our context and our contacts.

You play with a lot of pattern and design-like elements. What role does this serve in your work?

I see the patterns in my work as being directly related to language. In early works of mine, I would incorporate text directly onto the painting in order to anchor the figures to something that was present in the composition but which also completed its presence in the viewer’s own process of reading and interpreting the text. In language the word “tree,” when spoken to a group of English speakers, will provide a shared understanding of “tree” generally while, at the same time, evoking varied and often quite different images of particular species of tree in each individual’s recollection. I look for patterns that are descriptive enough to be legible, but general enough to recall different referents in each viewer. Through this, I hope to locate the figures in both the public and private sphere, in both a physiological and physical space.

The patterns in my paintings are often on perspectival planes that both situate and fragment the bodies they bisect—location becomes dislocation. A multiply situated subjectivity is central to my work, so I will emphasize simultaneity and multiplicity by pursuing patterns that offer a visual punning. For example, repeated flowers receding in space can exist as both a field of flowers in nature and/or as a manufactured pattern on a tablecloth or bedspread.

On the other hand, empty space has an equal if not greater role in your work. Why do you leave parts of the canvas seemingly bare?

When I entered grad school, I had been making large scale drawings on paper and I was eager to transform my practice into painting. I figured a logical first step would be to swap out my large sheets of paper with large pieces of canvas—a canvas ground was half way toward making a painting, right? What surprised me though was the scrutiny I got in crits questioning my decision to leave areas of the canvas exposed, a question that had never come up when I had made similar compositions on paper. I realized that while we are trained to ignore the paper in a drawing, the same is not the case for canvas and painting. Just by switching from paper to canvas, I experienced the full weight of the expectations and regulations that accompany painting.

I find the baggage that comes along with painting, the unspoken but highly regulated historical context that structures the legibility, taste, and value of a painting, to be a useful medium to unpack identity and what it is to live in a body. Sociohistorical ideals that are Western, heteronormative, patriarchal, white supremacist, maintain their status quo in part by operating under the radar of being natural and given. For identity, this takes the form of essentialist notions of biological determination, while in painting, this takes the form of the so-called genius painter who makes works that are inherently good.

Is there something in particular that you hope a viewer of your work walks away with?

One of the things I find most powerful about art is its potential to position people in a conversation they did not know was theirs to explore. I hope to make paintings that are a refuge for those of us who experience ambiguity on a daily basis and as a means to unlock the potential for ambiguity within those who have never had cause to question their own identity position.

At the end of every interview, we like to ask the artist to recommend a friend whose work you love for us to interview next. Who would you suggest?

So many! Lauren Satlowski, Cheyenne Julian, Julia Haft-Candell, Bridget Mullen, Jonathan Lyndon Chase, Nikita Gale, I could go on…